DAMIÁN ORTEGA

ON OBSOLESCENCE, SWEATY BOOKS, AND ASSEMBLING A LIBRARY OF PHOTOCOPIES. — JULY 3, 2019

Damián Ortega (b. 1967, Mexico City, Mexico) is an artist and the publisher of Alias. He lives and works in Mexico City and Berlin.

![]()

![]()

$55

Corinna Koch (for Zolo Press): Do you think it is possible that, one day, your daughters will look back to a time when people still had shelves full of books in their houses and realize that they are the last generation to have that memory—just as our generation is the last to know a pre-internet, pre- cellphone age?

Damian Ortega: It is shocking, this question, because it makes you think about how in a few months, weeks, days, or even minutes everything can change. I remember how analog photography simply disappeared and only a few stores remained that sold photo-paper, film, or dispositive slides. Or go out and try to find a landline telephone for sale somewhere! Yet, I do not think that this will happen to the book. I think it will last through time, as it has a very different approach to the world then the digital. My father was an actor and I remember that growing up there was always the fear that one day television was going to eliminate the theater, even the motion-pictures. But theater is a completely different language than television. Maybe people feel like television is a better fit for them—a more suitable medium for their lives, addressing their needs for commercial entertainment—but theater is a more human experience. There have always been, always will be, people who appreciate that.

CK: Would that mean that books become subject to a niche appreciated only by the few, transforming them from mass-medium to specialty? Like what’s happened with vinyl records?

DO: You know, a friend said recently to me that a book is like the internet unplugged. And also speaking of niches, you must remember that there are still many places on earth that don’t have internet. There are many other reasons why books could still be popular, as you don’t need anything to read them: no electricity, no devices, no internet connection, no accounts, no sensitive information being shared... You can simply open the book and start reading. So, I wouldn’t worry too much about the books. They won’t disappear. I’m more concerned about our disappearing concentration. Time to read, time to be focused, time to understand, and time to contemplate the things we read. That issue seems more difficult to me. What is being written is becoming shorter and shorter, and the ways of publishing faster. Everything is becoming more immediate. Even emails are too slow nowadays; things are arranged via WhatsApp. Yet, communication doesn’t become less; it increases constantly, stealing away our time.

“A BOOK IS LIKE THE INTERNET UNPLUGGED.”

CK: But people are starting to get tired of the screen. Audiobooks and podcasts are getting more and more popular—a comeback of the storytelling tradition, it seems.

DO: I like listening to audiobooks. Especially for my line of work, it comes in handy. And yet, it is very different from really engaging with a book, reading at your own pace. Curiously, the voices chosen for audiobooks are much lighter than the ones I give the characters in my head when reading.

CK: I’ve noticed that when I read certain passages, I become submersed in my own thoughts. A sentence or a word becomes a tripwire, sticking out from the text, signaling almost visually to stop and engage into a thought. I wasn’t even conscious of that, of how the written word gives you the freedom to engage in thought, and the duality it creates by that.

DO: I experienced something similar when I started Alias and the question of how information travels became an important concern. I mean, we grew up in the seventies and eighties. But during the nineties, when the whole thing about personal computers started, something changed. I remember when I started high school, my whole class went to visit the house of the only guy we knew who had a home computer. It was a bar mitzvah gift: the first Apple computer, a box-shaped thing that looked like a Danish cookie tin. Such a novelty. I remember that I found it truly beautiful. It would take some years to reach the boom that we have now. But even back then information travelled, and I remember how some of the richer kids from school vacationed in Europe regularly and would bring back books which we then would make photocopies of and exchange. It was visually interesting, all these different viewpoints on the texts, and the personalized libraries of pinned- together, photocopied books that were created in this way. This also created a human exchange, you know? To meet up with friends, and talk about the books you are reading, and what you think about them. And then there was, and still is, the secondary market where you can buy old books, and this again creates a very nice exchange.

CK: The content becomes an object, a thing that possesses a soul, almost. Or at least a commodity that becomes part of your household, that co-exists with you.

DO: Exactly. But also a thing that provokes human exchange—dialogues. And evokes places.

CK: Are you trying to recapture the experience of these pinned-together books with Alias?

DO: In a sense. We are trying to avoid distribution, for instance. We try to find and speak directly to our readers. It started with us going to art schools, events, and conventions and trying to sell our books out of a rolling display cabinet—you know, the ones that they use on the streets for selling potato chips and chicharrón. I bought one of those. It smelled and was sticky all over with spilled chili-sauce, so I had to wash it down multiple times, and it still smelled for weeks. It was amazing, because the students were very familiar with this type of rolling glass cabinet, and everyone understood the joke of the intellectual re-contextualization. So we started to sell books like this, in a very informal way.

CK: What do you think is the political role of the book today? I mean, they really used to be bombs of information. The earliest books transmitted ideologies, and then, during the last century, the political book took on the role of vessel for major shifts in thinking. From Martin Luther’s translation of the bible, to Karl Marx’ Das Kapital. Do you think that books still have that power to change the paradigm? Of course there are books like Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, but...

DO: I think so. You know what I find amazing, really amazing? With Alias we never printed a large amount of copies, and yet I’m quite sure that each book we make and sell transforms everything. I’m not interested in quantity. I believe that political change comes by planting one idea at a time, getting into the head of one person at a time. Just one person can transform the idea of what art is, what culture is, and what her or his role is in it. Simple as that. Because if one person can transform his or her idea into something as real as a book, that passage might become something very influential for another person, for a community, for a country, for a world. And it is just one. One book, one person.

“JUST ONE PERSON CAN TRANSFORM THE IDEA OF WHAT ART IS, WHAT CULTURE IS, AND WHAT HER OR HIS ROLE IS IN IT.”

CK: Like ships or space shuttles sent into the unknown. Each carries a mission and a name, has a certain identity...

DO: That’s why we chose the name Alias, because it does not only give a label to the publishing house, but also acts like a proper name. I know the transformative power of books from my own experience. I’ve read such a book.

CK: Which one?

DO: Octavio Paz’s Apariencia Desnuda: La Obra de Marcel Duchamp! It was through the book that I learned about Duchamp, and it was a revelation. I’d read it over and over again. I’d carry it around under my arm. I like the idea of sweat—

CK: The sweaty book?

DO: The underlined book, the book that has edges curved from carrying it around in the back pocket of your trousers. Your book. How many books can there be that will have such an impact on your life? I think that we really overvalue quantity today. And we overvalue speed. We tend to prefer immediate answers to the ones that grow on you. What impresses us most is impact. How many people have seen it, how many have liked it, how often it has been cited, and all that. Books refuse to deliver to these measures.

CK: But they are becoming like that, or at least the statistics say that more books are sold today than ever before but people seldom actually read the books they buy. It becomes about possession and abandonment—just another object in consumerism’s cycles of production and discharge.

DO: And visual culture. I can also see that in art, the way that it is becoming more visual, more glamorous again.

CK: And, of course, the books that sell best these days are intended for coffee tables. How do you approach that dilemma? How do you distance yourself from those fast food books—the glossy, glamorous Taschen-variety—while also creating a strong visual language for the books you publish with Alias? How do you draw the line? And how do you get people to actually read the books?

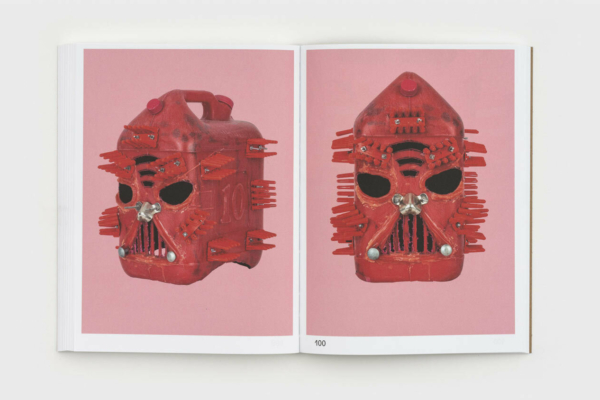

DO: I guess the answer is always to assume some limitations. I mean, I cannot compete with the hyper-visuality of those coffee table volumes. I can’t fight an internet where you can find hundreds of images of Duchamp’s works, razor sharp and in perfect color. This is not what I need to transmit; they are already accessible for everyone on the web. What I want to give is a good text in harmony with the images so people actually understand what it is they have in front of them, and what it might be for them. So I don’t worry so much about the quality of the image. To me the idea is what counts.

CK: And you also edit the information, shape it into a form.

DO: You create a complete system in the book which helps you to understand that idea. But also what I am trying to tell you is that the seduction can come at a high or low price. Because books have also always been about seduction. They need to create an interest, a curiosity, and they need to provoke a certain experience for the reader. I realized this in all my visits to bookstores. And I came to understand that what is happening to the books I once knew is very similar to what is happening to art: things are starting to look more and more homogeneous. There is a certain aesthetic that is guiding everything and almost no one seems to be willing to break away from that visual consensus. The materials, the sizes, the colors—they all seem to follow the same strategy. I like to see my books nestled between the others on those shelves. A little off in their colors, a little poorly done, a little deformed. I like the modesty they suggest. The wannabe hipster that tried a bit to fit the standards, but then realized he couldn’t really be bothered by effort. I find that charming. Way more charming than the overproduced guy reaching for perfection.

CK: The small flaw in the perfect picture. Slavoj Žižek suggests it is those little flaws we notice about someone that we most cherish, that make us fall in love. My Funny Valentine... Talking about special characters: what do you think José Guadalupe Posada, Mexico’s most famous political printmaker and engraver, would be doing if he were alive today?

DO: Absolutely the same thing!

CK: Really?

DO: I think so. I mean, he was a master of his technique.

CK: I could also picture him making some really good memes.

DO: You have a point. It is interesting: I am a strong supporter of books and printed matter. But I don’t want to come across as reactionary. You know? I mean, I realize things are changing rapidly and a new language is being created which I’m not necessarily familiar with. But something is happening and these processes are always amazing. Just take Luther again and the way he used that brand new technology of printmaking back then when he published his translation of the bible.

CK: Unimaginable. Before that there only existed one or two copies of each book. They were handmade, and a monk spent his lifetime on one copy, writing the texts, and illustrating them—his way of thinking, his ideology slowly seeping into the book, changing its content, leaving out what he personally just couldn’t agree with... In a way, the internet functions like that again nowadays. Because it forms bubbles around people, and you only learn about things you already know, and with which you agree, transmitted by people who share the same views as you—preaching to the choir. Information becomes just another commodity, fit to your needs. Like the algorithm that tells you “if you like that, you might also like this.”

“AND THE SYSTEM BECOMES FASTER AND FASTER IN ABSORBING EACH NEW TENDENCY [...] RADICALISM AND AVANT-GARDISM BECOME VIRTUALLY IMPOSSIBLE.”

DO: And the system becomes faster and faster in absorbing each new tendency, each sub-cultural movement or aesthetic. A thing sells out a few moments after its creation. Radicalism and avant- gardism become virtually impossible.

CK: As an artist and someone who makes books, what do you think about the notion of creating something for the afterlife? After all, books and artworks are things that, at least until now, had the tendency to transcend time?

DO: This question makes me really scared! I guess in a way I am really irresponsible; I should be sending bottles to the future. Instead, I keep on trying to understand what is going on in the present. That’s the core of my work, and that is the only thing I know I am capable of resolving! But being in the present also means that you are creating links to other contemporaries. There is a whole network of communication between the artistic work that is produced in the now. It happens very naturally, very organically, very authentically. I find that very exciting. And I like the honesty and modesty in that posture. It’s not my business to try to predetermine what people might think about all this in the future.

DAMIÁN ORTEGA INVITES YOU TO READ:

- The Death Ship, B. Traven

- The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, B. Traven

- The Bridge In the Jungle, B. Traven