CHARWEI TSAI

ON WRITING, IMPERMANENCE, AND WRITING IMPERMANENCE.—05.29.20

Charwei Tsai (b. 1980, Taipei, Taiwan) is an artist and the publisher of Lovely Daze, a journal of artist’s writing.

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): As a child, you memorized the Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya—the Heart Sutra. Do you remember first encountering this scripture?

Charwei Tsai: Across Taiwan, the calligraphic form of the sutra is commonly displayed on scrolls in homes and temples. It is just as frequently chanted at Buddhist ceremonies and funerals. I had memorized the text by heart since childhood and recited it for protection when I had nightmares or was confronted with fear.

When I began copying the sutra myself I was not aware of the rich Chinese sutra copying tradition. The tradition began in the Tang Dynasty when many Buddhist scriptures were first translated from Sanskrit into Chinese script. Patrons would commision monks to copy sutras, which were believed to cultivate merit in one’s ancestors, family, and self by the transference of their sacred outlook.

Z: Do the sutra’s words have a particular form in your mind? How do they look? Sound?

CT: They appear in my mind in the form of calligraphy. On a more subtle level, they resonate as an open space.

Z: The Prajñāpāramitāhṛdaya lies at the heart of your practice. As you have moved from writing to drawing, photography, and film, you have carried this scripture with you. How has this chanting—textual, photographic, filmic—transformed the text for you?

CT: Eye consciousness has always been the strongest sense through which I relate to the outer world. Therefore, writing the text on ephemeral materials and visualizing the text’s dissolution aids my understanding of the text. I see my practice of art as a medium for internalizing Buddhist teachings through sense consciousness, particularly those teachings on appearance and emptiness.

“writing the text on ephemeral materials and visualizing the text’s dissolution aids my understanding of the text. I see my practice of art as a medium for internalizing Buddhist teachings through sense consciousness”

Z: You’ve been working with the Heart Sutra since 2005. It is still giving to you, some fifteen years later.

CT: Absolutely. The text has changed for me in different stages of my life. When I was younger, I’d recite it for protection when I was scared. When it became a part of my art practice, writing it was a way of processing the relationship between form and emptiness. And now during the pandemic, as I have been meditating more, the text has become a guide of how to rest in a non-dualistic state where the subject and the object of meditation dissolve.

Z: Have you ever written alphabetic transliterations of the sutra? Or do you insist on its pictogrammatic rendering?

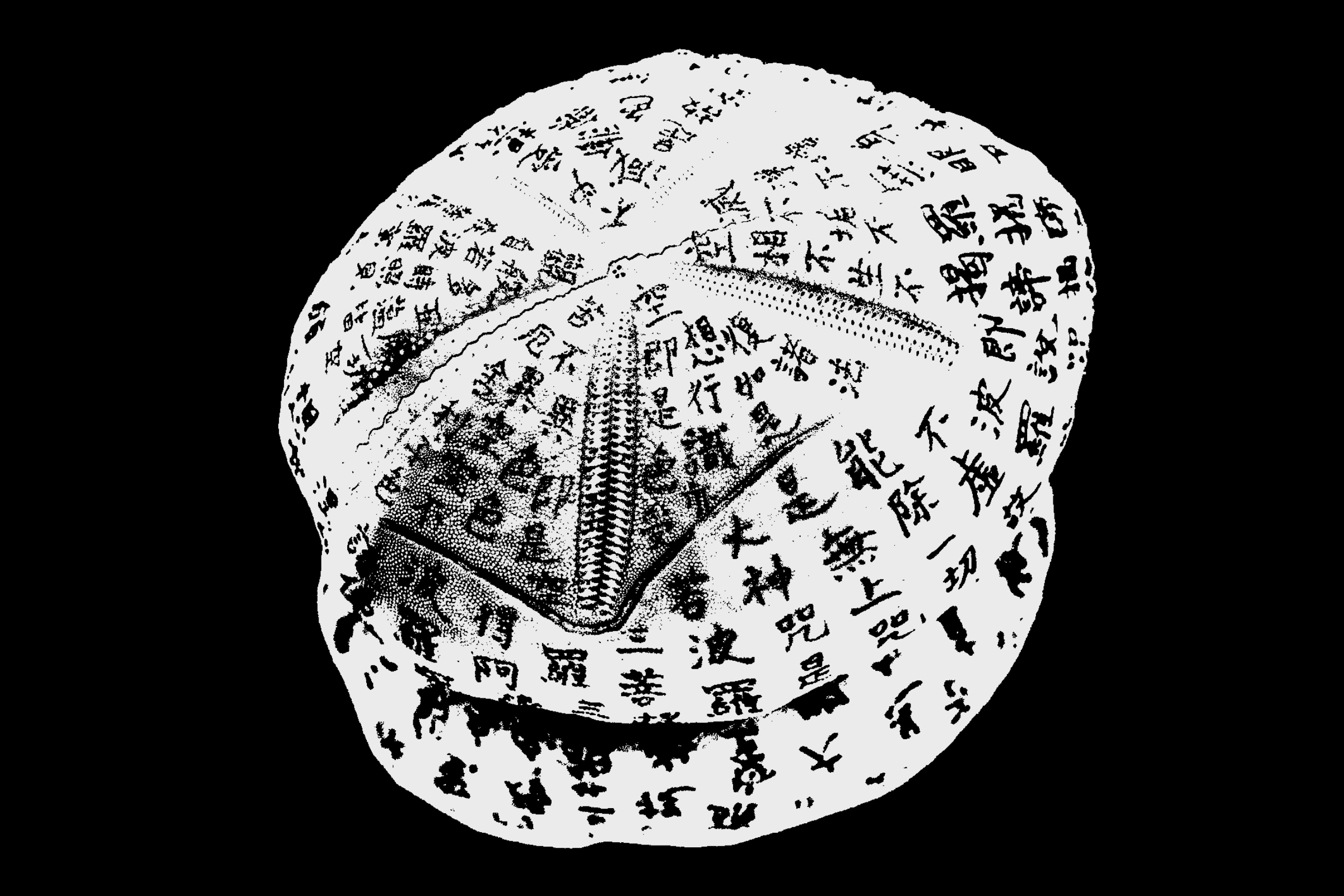

CT: I stick to the pictograms. In Chinese, a text can be written in several directions: top to bottom, left to right, right to left. This allows me to echo the shapes of the organic forms on which I write more easily than a transliteration would. For instance, when writing on trees I direct the text along the woodgrain. On shells or the heads of mushrooms the text becomes a spiral. Plus, there is a certain embodiedness in calligraphy. As my arm moves with each word, I try to contemplate and internalize its meaning. Sometimes writing a word feels like what it means. The pictograms for sun and moon, for instance, conjure the words. When the two words are written together as one character, the meaning becomes luminosity.

“when writing on trees I direct the text along the woodgrain. On shells or the heads of mushrooms the text becomes a spiral.”

Z: In comparison to the ephemeral materials on which you typically write, the book is a remarkably durable form, unchanged since the fourth-century Codex Vaticanus of the Christian church. You have made several books yourself, most recently Root of Desire (2019). Is there friction between the printed page’s relative permanence and the impermanence of the other “pages” you write on?

CT: I don’t think of books as permanent. Sure, they last longer than mushrooms that decay before your eyes in one day. But alongside bones and shells, the book’s impermanence comes into focus. All compounded things disintegrate; that is the basis of the Buddhist view on reality.

Z: Language—the stuff of books—is itself impermanent. An etymology is to a word what rings are to a tree. When a new ring begins to grow, we say that that word is "semantically drifting." In the process, it "narrows" and "widens" like the banks of a river at low and high tide. Some words even become "skunked": difficult to use because they are transitioning from one meaning to another.

“I don’t think of books as permanent. Sure, they last longer than mushrooms that decay before your eyes in one day. But alongside bones and shells, the book’s impermanence comes into focus. All compounded things disintegrate”

Z: Language—the stuff of books—is itself impermanent. An etymology is to a word what rings are to a tree. When a new ring begins to grow, we say that that word is "semantically drifting." In the process, it "narrows" and "widens" like the banks of a river at low and high tide. Some words even become "skunked": difficult to use because they are transitioning from one meaning to another.

CT: True. Nothing is spared from change.

Z: The Tibetan Buddhist lineage of which you are a part focuses on oral chanting. In your most recent work, you have focused on the spoken word. Songs of Chuchepati Camp (2017) documents the voices of Nepalese earthquake victims. Hear Her Singing (2017) records the hymns of refugees and asylum seekers currently living or detained in the UK. Can you speak about your interest in singing and the relation between suffering and song?

CT: I was invited to Nepal by The New School in New York as part of their program with artists of American, Chinese, and Indian origin. While there, I wanted to visit my Buddhist teacher’s teacher, a Tibetan lama who is known for singing as a way of transmitting his spiritual realizations. His presence radiated wisdom and compassion inexpressible by words, and I was inspired to make a work using the powerful expression of songs.

On my second trip to Nepal, while searching for subjects for this new project, I came across a makeshift camp of earthquake victims. This was two years after the major earthquake in Nepal in 2015 and tens of thousands of people were still living in devastating conditions. Together with a Tibetan filmmaker and a local Nepalese director, I went around a camp in the middle of Kathmandu and invited the victims to share songs that expressed their current situation.

Many cried and laughed while they were singing. I ended up continuing this project of recording songs by people whose voices are not often heard, including songs by female asylum seekers in a detention center in the UK and migrant boat workers in a harbor in southern Taiwan. All the songs share a similar sense of despair of being separated from their loved ones or a hope of being in union with them. These songs remind us that the core values that we share as a humanity in the end are far deeper than what divides us.

Z: In 2005, the same year you began working with the Heart Sutra, you founded Lovely Daze, a biannual art journal, to "provide a platform for artists to present, first hand, their writings and artworks." What called you to this?

CT: The first exhibition in which I participated was held at Fondation Cartier in the summer of 2005. There was a group of sixty artists from all over the world who were younger than thirty and had never exhibited previously. We had such beautiful and memorable exchanges. After getting to know the artists on a personal level, I realized that what critics wrote about their work had almost nothing to do with their intentions or the work itself. After returning from Paris to New York, I was inspired to start a platform to present artists’ works alongside their own writings.

“After getting to know the artists on a personal level, I realized that what critics wrote about their work had almost nothing to do with their intentions or the work itself”

Z: Alongside Lovely Daze’s more established contributors like Yoko Ono, Vito Acconci, AA Bronson, and Alfredo Jarr, you reserve space for artists who have not previously published.

CT: Yes. I always feel like a beginner or an outsider in everything that I do and I have learned there is great value in this unpolished approach to art. So it's important for me to keep including voices that are not often heard. For the Lovely Daze special editions, I also publish artists who come from other disciplines: like a cookbook made in collaboration between a pastry chef and a painter, or the journal of a photographer who documented life around the Colombian coast where Gabriel García Márquez wrote A Hundred Years of Solitude. It would simply be too limiting if I were only to publish artists who are already circulating in contemporary art platforms.

Z: Do you work with these artists to conceive of their contributions?

CT: It depends on my relationship with the artists. With close friends, I am able to demand a lot more of their time and to ask for original artworks or writings that are created especially for the issue. For some issues, there are specific works that I have in mind by well-known artists who I may or may not know personally. In this case, I try to find their contact and request for those specific works. For example, I have published some of the earlier, signature works and writings by artists like AA Bronson and Vito Acconci. There are always surprises in the preparation stage as well. I invited Yoko Ono to contribute a piece to the fourth issue. Much to my surprise, she responded personally and instructed me to mirror the image of her album cover for "Walking On Thin Ice."

Z: Each new issue is inaugurated by a performance.

CT: Performances have always been a vital part of the launch of each issue and have become like a ceremony to initiate each issue into its material existence. The performing artists again vary widely from Mark Borthwick to Lizzi Bougatsos to Howie Chen and James Hoff, all of whom I met while living in New York. As I spent more time in Asia in the last few years, I am starting to discover many wonderful artists here as well. For example, the most recent issue of Lovely Daze was inspired by the Mongolian pop song “I Wish I Had A Horse.” It’s a phrase that describes young Mongolians’ sentiments of feeling lost in their urban lives and longing for a deeper connection with nature. For this issue, I invited Mongolian artists Ganzug Sedbazar and Davaajargal Tsaschikher to perform at two art spaces in Taipei. Each performance opened up a different world view of how we relate to animals and to our natural environments.

Z: Before founding Lovely Daze you worked at Printed Matter. How did you arrive there?

CT: After I graduated from the Rhode Island School of Design, I moved to New York City. That was just a year after September 11, 2001; as you can imagine, it was not the best time to find a job. I sent two hundred resumes at random to every art and design place around. Printed Matter was one of them, and they happened to have an opening for a part-time position. It was the best. Everyday I discovered new artists and ideas. Many of the people I met there I still stay in touch with. My time at Printed Matter inspired me to start a publication of my own.

CHARWEI INVITES YOU TO READ:

- The Art of Encounter, Lee Ufan

- Language to Cover a Page: The Early Writings of Vito Acconci, ed. Craig Dworkin

- Negative Thoughts, AA Bronson