CARYL BURTNER

ON SUPERSTITIONS, SLEUTHING, AND SECRET HISTORIES—04.28 / 05.17.2022

Caryl Burtner (b. 1956, Washington, DC, USA) makes art for her sake and about her everyday life. She lives and works in Richmond, Virginia.

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): 1976, Richmond, Virginia: you are in your second year at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) when your apartment burns down. You notice, amidst the still smoldering ashes, your toothbrush. You decide to save it. What attracted you to that toothbrush?

Caryl Burtner: When I bought that toothbrush I had no idea that tragedy would befall me while using it. I kept it, and I started thinking: when we buy something—like a box of salt, which is going to last a year or more—we just don’t know what will happen within that time span. It’s ominous.

ZP: You have collected over a thousand toothbrushes since.

CB: It’s true. After the fire I wanted to thank the friends who had supported me, and I decided to throw them a dinner party. This is actually where the collection began. As the price of admission, I asked them each to bring a toothbrush that they had been using at the time of the fire and to complete a form with its details: make and model, place of purchase, dates used, purpose (if other than dental). I then numbered the toothbrushes and information forms. When I began to exhibit the toothbrushes some years later, they were labeled and the viewer could look up their histories on the corresponding forms in a nearby binder.

I must say, toothbrushes just aren’t pretty any more. In the old days, you could find them in a bouquet of colors. Now they look like athletic shoes, you know. I live in a house built in 1919 and I can’t even fit the new ones into the tile toothbrush holder; they are too big.

ZP: Amongst your collection are toothbrushes given to you by artists like Kenny Scharf and John Baldessari. What especially intrigues you about the domestic paraphernalia of these celebrities?

CB: Everybody has a toothbrush! Warhol noted that mid-twentieth-century American culture was the first in which the rich and poor bought the same things and used the same products. For a long time I wanted to be a psychologist. I was fascinated by personality tests; I always thought there must be some reason why disparate people all choose the same deodorant.

Jasper Johns was the most famous person to reply. His assistant sent an empty typed envelope that said, “Jasper Johns is unable to respond to your request.”

ZP: Did you always have this itch for collecting? Or was it inaugurated, or intensified, by the suddenness of the fire?

CB: I collected trolls and Barbie dolls like most girls my age but I also gathered information. In this I was inspired by my two childhood storybook heroines: Pippi Longstocking, who was a curious free-spirit, and Harriet the Spy, who documented everything. Back then I spent a lot of time with my coloring books in front of the TV. I remember a commercial that announced, “This bra has been machine-washed fifty times and it still stretches like new!” I thought, Wow, a grown-up counts the times she washes a bra? That piqued my curiosity so I decided to try it myself. I counted every time I heard Nat King Cole’s “Lazy Hazy Crazy Days of Summer,” which I loved. I was about eight then.

Some say that hoarding can be a symptom of trauma or loss, and one of my professors in graduate school was sure that my fire had messed me up. He suggested psychiatric help. I dropped out of that program after one semester.

“I remember a commercial that announced, “This bra has been machine-washed fifty times and it still stretches like new!” I thought, Wow, a grown-up counts the times she washes a bra?”

ZP: Two years after the fire, you began your “exercise in triskaidekaphobia” by removing a one-inch square around the number of the thirteenth page from the volumes in your library. You would later gather these clippings in the artist book The Exorcism of Page Thirteen (1993). How did this exorcism start? What needed exorcizing?

CB: It began with my interest in superstition. I’d always been eager to know which drinking glass or coffee mug or toothbrush would bring me the best luck. Was it the pink Oral-B or the blue Colgate? The notion of a gridded collage of page numbers began as an assignment in college when I still thought I wanted to be in commercial art; the teachers quickly discouraged me from that. We were tasked with making a graphic design with subtle variations amid repetition. For some reason I chose the number fifty-two and cut it from every book or magazine I could find. Then, some years later, it dawned on me: I should do this with thirteen. Originally I cut out the whole page and used binders with the squared numbers in the front and the pages in the back. If a word intrigued you in the collage or you thought you recognized it from a book, you could look it up. Then I started to feel bad about removing an entire page.

The series has continued—and undergone many changes. I just made another one from Paul Auster’s Leviathan. I maintain that it improves my luck by getting rid of the thirteens. At the very least, it is really fun to buy a new book and discover what’s on the thirteenth page. And sometimes there is no thirteenth page whatsoever.

“I’d always been eager to know which drinking glass or coffee mug or toothbrush would bring me the best luck. Was it the pink Oral-B or the blue Colgate?”

ZP: Like buildings that skip the thirteenth floor.

CB: I love that, don’t you? Isn’t it crazy that all the developers and contractors would agree to skip the number thirteen? It reminds me of Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas.

Now, what about table thirteen at restaurants? Who knows what sort of fights and breakups happen there. I have begun going to restaurants around town and asking the host to point out table thirteen. I intend to alert people to table thirteens so that superstitious folks will know not to sit there. I have also been documenting the things that happen to me on Friday the thirteenth. So far, nothing especially disastrous has occurred.

“I have begun going to restaurants around town and asking the host to point out table thirteen. I intend to alert people to table thirteens so that superstitious folks will know not to sit there.”

ZP: Speaking of the Dictionary of Received Ideas and its parody of clichés, in 1986 you made Look Before You Leap, displaying a string of paradoxical idioms on a billboard: “Look before you leap; he who hesitates is lost!…Familiarity breeds contempt; to know me is to love me!…Honesty is the best policy; what you don’t know can’t hurt you!”

CB: Yes. Basically, I wanted to showcase the humor in taking “received ideas” at face value and to offer people a choice as to which expression to believe. I think that two mutually impossible concepts can each be truthful at the same time. I was proud to be selected to create that billboard. I won five-hundred dollars, which was a lot of money at the time.

ZP: You have credited a William Wegman video as your original inspiration. What compelled you about this piece?

CB: I didn’t know much about performance art when I arrived at VCU, but when a sculpture teacher named Joe Seipel showed the class the humorous videos that Bill Wegman had made with his dog Man Ray, I realized that the little games I’d been constructing for myself all along were an art form. Play = Art was a breakthrough.

I was a Beatles fan and naturally curious about Yoko Ono, so I bought her book Grapefruit when I was young. I loved it. Her instructions for performance were at once whimsical and deeply profound. This was art, too! For example: “Pea Piece: Carry a bag of peas / Leave a pea wherever you go”; or “Syllable Piece: Decide not to use one particular / syllable for the rest of your life. / Record things [that] happen to you in / result of that.”

ZP: Your work has been described as endurance performance for its sheer exhaustiveness. In addition to recording the goings on of Friday the thirteenths, you’ve logged every date on which you have played a record in your collection and the precise shoes you’ve worn each day (“Candies,” “Black Satin #1,” “Black Satin #2,” “Italian Sandals,” “White Slippers,” etcetera); you have photographed every pill, spice, and shampoo bottle you’ve used alongside its price and provenance; and you have noted each word you’ve looked up in the dictionary. You play between temporalities: the ephemerality of the acts you document and the durability with which you document them.

CB: I appreciate that word—exhaustive. Honestly, exhausted is what I am. It is a lot of work to compile all of this, but I feel that I am meant to count things and develop systems for documentation. It’s just the way my mind works. I am storing the present on an imaginary timeline for future reference. It allows me to search for connections, witness collective memory, and demonstrate gradual societal change.

Recently my methods have changed. I am now working with Excel charts. When I was young, before anybody really had a personal computer, I used to think, Gee, I wish I had a machine that would compile, classify, and organize all of this information. Now I do. I have also been working on more practical things, like a mosaic backsplash for my kitchen.

“I am storing the present on an imaginary timeline for future reference.”

ZP: When you aren’t dilating time, you are compressing it. 100 Best Books, Abridged collects the first and last lines from each of Random House’s 100 Best Books of the 20th Century: for instance, from Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, “The North Carolina Mutual Life Insurance agent promise to fly from Mercy to the other side of Lake Superior at three o’clock. For now he knew what Shalimar knew: If you surrendered to the air you could ride it.”; or from Virginia Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, “‘Yes, of course, if it’s fine tomorrow,’ said Mrs. Ramsay. Yes, she thought, laying down her brush in extreme fatigue, I have had my vision.” How do you choose what to elaborate and what to abbreviate?

CB: Excerpting the first and last lines saves people from having to read the whole thing. At first 100 Best Books, Abridged was satirical. The Random House list was something like ninety-two percent American men and I was poking fun at its self-importance. I also wanted to be playful with it because I love to read—I love books. More generally, I elaborate on what I believe will be interesting from a vantage point in the future.

ZP: For many years you worked with more hallowed archives—Old Masters rather than Old Bay—as the administrative coordinator and curatorial liaison to the registrar at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. How did the museum’s archival processes inform yours?

CB: Well, I did learn the word provenance. When I started they still used index cards for object documentation. I would type the cards and, as time went on, the curators would make pencil annotations: “this attribution has changed,” “new dates have been discovered here,” etcetera. You could see layers of understanding deposited over time. Now that we have databases, that sedimentation is lost. Think about library books. Each one used to have a checkout card with the name of everyone who had borrowed that book before you. Sadly, that information is now secret history. I am very interested in those secret histories and that lost information. In a sense, I am working against secrets and loss.

These themes inform two of my favorite artworks. There is Dario Robleto’s piece where he melted down Billie Holiday records, formed buttons out of the molten vinyl, then sewed the buttons onto a shirt which he then gave to Goodwill. Someone is walking around not realizing that Billie Holiday tunes are embedded in their shirt. And then there is Spencer Finch’s installation of one-hundred drawings of various shades of pink called Trying to Remember the Color of Jackie Kennedy’s Pillbox Hat.

“In a sense, I am working against secrets and loss.”

ZP: Secret history. Your method has been analogized to that of an FBI agent. “Information is gathered, sifted, collated; results are documented and filed, and connections are made. There are no days off.“ Of course, you are your own suspect. “The devotion to duty here suggests a higher calling, as to public service.” Tell me about the public service of examining your private life.

CB: I have come to think about it as monastic work. I make things that are interesting to me and allow me to understand my life; hence my motto, “Art for my sake.” Recently, however, Richmond’s history museum has grown interested in acquiring a large portion of my early work because it tells the story of an eighteen-year-old girl who arrived in Richmond, went to Virginia Commonwealth University, lived in the dorm, bought her shampoo, took the bus, and got an apartment on Grace Street with her friends. It seems mundane but may prove fascinating in another century—at least so the director thinks.

ZP: The public service of private life recalls, of course, second-wave feminism’s insistence that the personal is political. Indeed you were coming-of-age when another Caryl—Carol Hanisch—popularized the phrase in ‘69.

CB: Right. When I was at VCU in the Seventies, I was an active member of the Women’s Caucus for Art, the national feminist organization that spawned the Gorilla Girls. I remember that after a group show at the Jewish Community Center, where I debuted my first four Exorcism of Page 13 pieces, one reviewer stated that I was making collages just like the ladies who scrapbook. I was irate. No, I wasn’t!

It is self-evident: the personal is indeed political. It’s interesting that many second-wave feminist artists responded enthusiastically to my appeal for toothbrushes: Linda Montano, Martha Rosler, and Carolee Schneeman, to name a few. The most overtly feminist piece I have made was a collage of all the boxes of birth control pills I took over a period of time.

ZP: In Bride’s First Signature, you collect the moments (on napkins, gift wrapping, and other marital ephemera) women first write their new names. Of this you have said, “in some cases this metamorphosis would be taken in stride. But on other occasions the significance of this small event would surprise the bride herself—in the act of writing her new name she would realize that now, in a sense, she was somebody else.”

CB: It’s true. That began when my cousin Sherrie married a man named Stephen Punko during the height of the punk craze. I was amused by his name, and at the reception I asked her to write “Sherrie Punko” on the paper tablecloth. We sensed a transformation; we felt a certain awe. This was her new world.

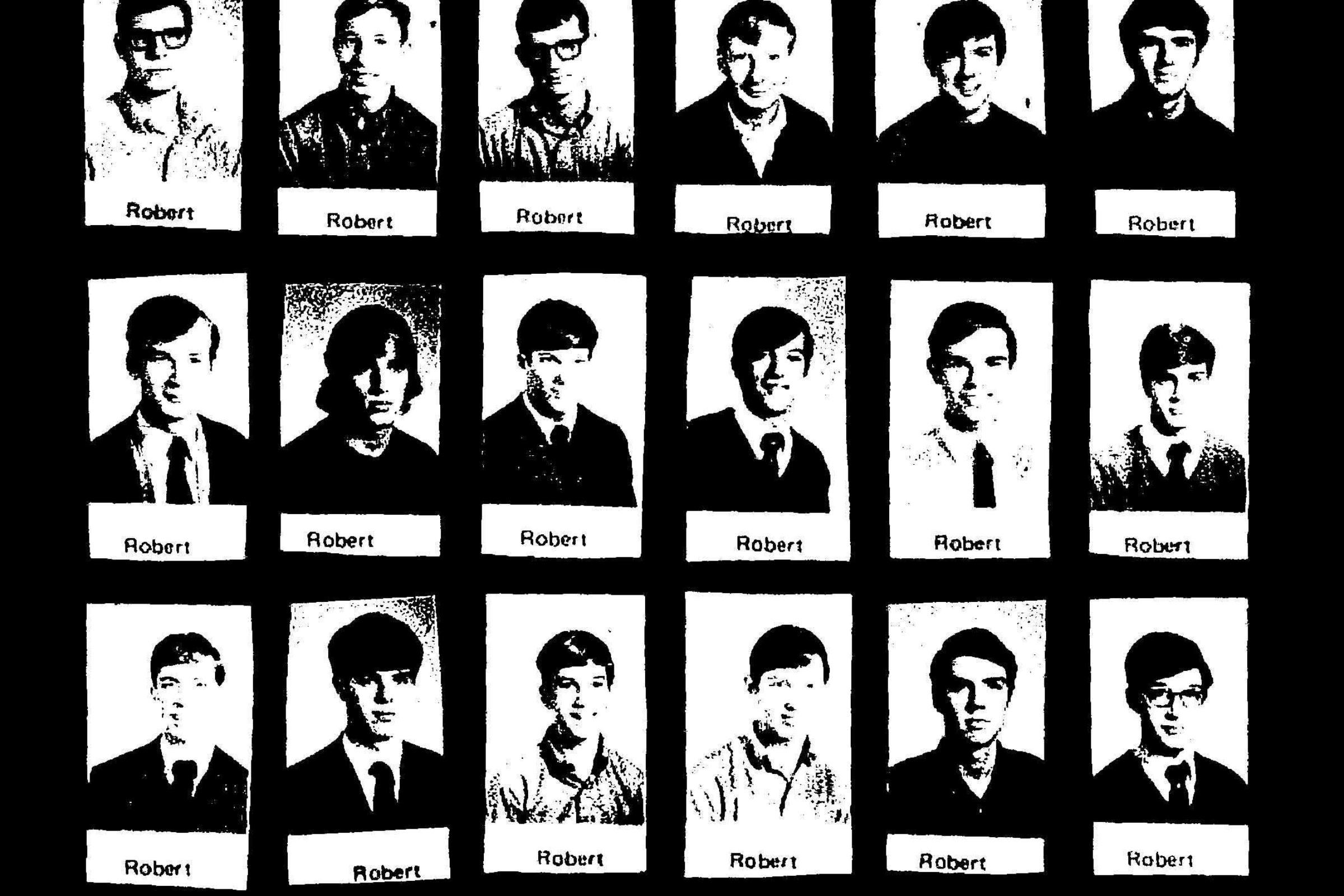

ZP: You have elsewhere reflected on the arbitrariness of names, like in compiling the photos of all the Carols that appear in yearbooks. Likewise, Lipstick Blots documents the names of lipstick colors—“Forward Fig,” “Mochaccino,” “Very Berrie”—and Crayons compares the colors of generic and Crayola crayons of the same name—“Indian red,” “Plum,” “Goldenrod,” “Sea green.”

CB: I am fascinated by names. I buy every baby name book I can find. Are they arbitrary? I am interested in them from a historical, sociological, and metaphysical perspective.

I recently read this in The New Yorker about Tom Stoppard: “Stoppard is ever-alert to the plump comedy of…words that are confusingly shared by people and things.” I am, too! When I was a little girl, the two big girls in my life were named Collie and Penny. I was perplexed that Collie could be a dog and Penny could be a coin. It blew my mind. Polyvalence has informed so much of my work since.

I have to confess: the irony of all of this is that I am really a very private person.

CARYL INVITES YOU TO READ:

An Anecdoted Topography of Chance, Daniel Spoerri

The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B & Back Again), Andy Warhol

Alloy of Love, Dario Robleto