HANA MILETIĆ

ON MINOR GESTURES, SLOW STUDY, AND TOUCHING IMAGES—07.29.2022

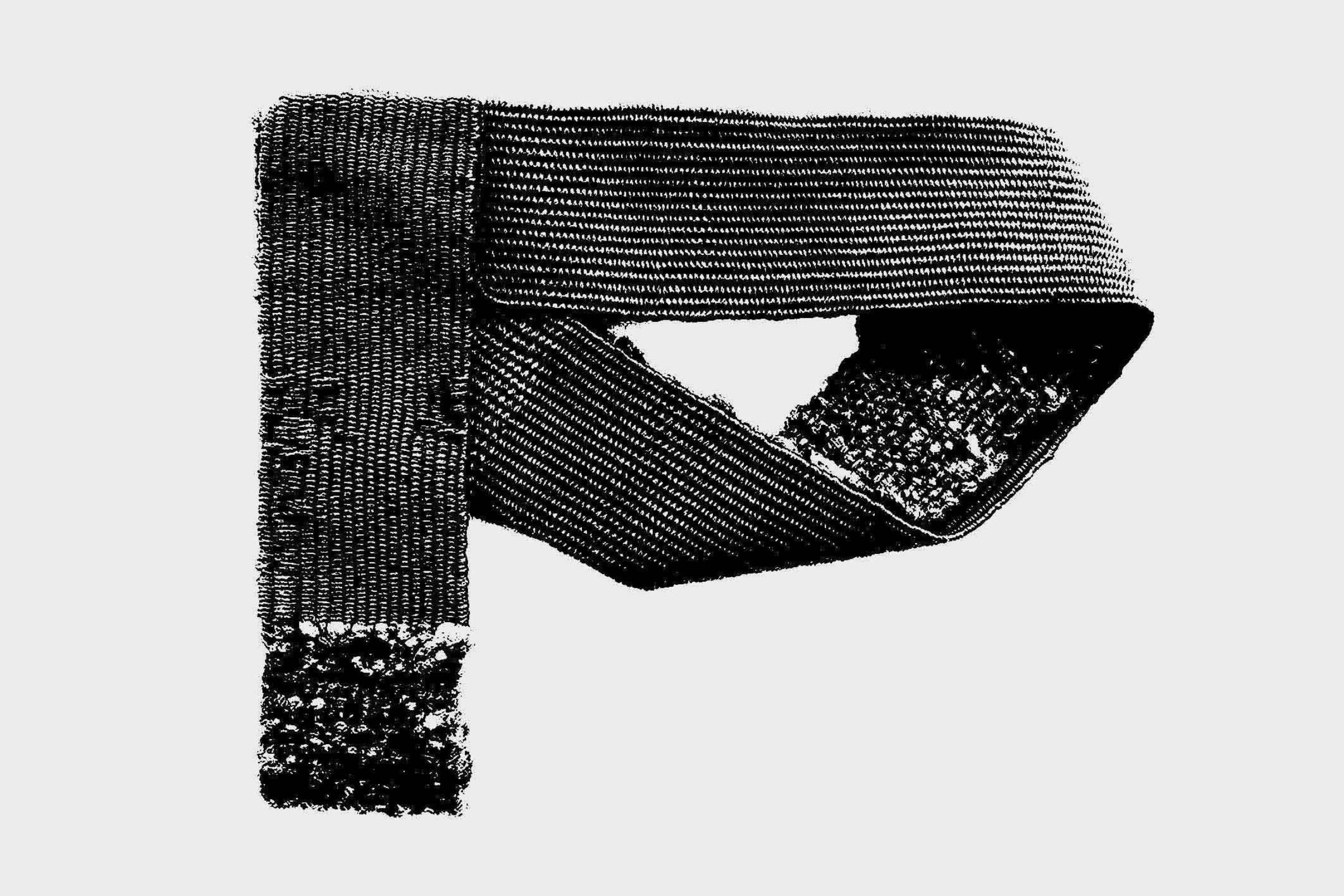

Hana Miletić (b. 1982, Zagreb) makes cartoons of everyday repairs and translates them—no, reproduces them—in woven textiles.

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): You document repairs—the broken windows patched with duct tape, the decapitated car mirrors held precariously in place with twine—with your camera and then abstract these repairs on the loom. Do you think of this abstraction as translation, with its ambition to preserve, as faithfully as possible, its referent in new form. Or is there another transformation—another act—that feels more apt? You have called your weaves “reproductions.”

Hana Miletić: I trained as a photographer; photography is my original medium. I began weaving out of frustration with photography. I always had the sense that I was taking stuff from the street that I was not entitled to. I’d then process the film without much awareness or care, as if its development was just incidental. None of this felt situated. You could, of course, say that I am still taking things that don’t belong to me, but in weaving these repairs my body is so much more involved. It’s a very lengthy and slow process that demands a sincere dedication to the act of reproduction.

I don’t consider the transformation from photograph to textile translation. If anything, it is study. I started weaving to better understand the repairs I was photographing: the individuals involved, the humdrum materials they employed, the minor gestures they performed, the geographies they occupied. Weaving gives me the time to reckon with all of this. It also allows me to disrupt photography’s visuality and situate images in the realm of affect—make them into haptic or soft images. I am not after translation; I want to move from one way of perceiving to another, from eye to hand.

“Weaving gives me the time to reckon with all of this. It also allows me to disrupt photography’s visuality and situate images in the realm of affect—make them into haptic or soft images. I am not after translation; I want to move from one way of perceiving to another, from eye to hand.”

ZP: You transpose images into a different grammar altogether.

HM: Yes. This transposition, however, doesn’t cancel the original photograph; I don’t want to reject it from the process. With photography, I never had the satisfaction of touching an image. Now I do.

ZP: Study, as Fred Moten and Stefano Harney remind us, always implies a public: “Study is what you do with other people.” You work alone, in the company only of your loom for the many weeks it takes to make each piece. Do you nevertheless feel a certain communion with the people whose repairs you are working from? Are you getting to know them?

HM: There is something intimate about the whole thing: about tracing a stranger’s hand gestures by weaving the tape that they used to patch a window or door or to reaffix a knob. All of the repairs that I reproduce are located in public spaces, so in that sense community is always implied. And, of course, weaving has long been a communal practice. The knowledge that I use has been transferred to me by many weaving teachers and ancestors. My maternal great-grandmother, for instance, was part of a weaving community in what was then Yugoslavia. Although the study may seem solitary, it is always connected to her and her fellow weavers. I wouldn’t be doing this without them.

ZP: When did repairs first pique your interest? And what, after seven years of your Materials series, sustains your interest?

HM: I’m not sure when I first became interested in repairs. Anyway, by the time I started weaving in 2015, I had accumulated a small archive of photographs. I knew I didn’t want to work with these images archivally; I didn’t want to categorize them, taxonomize them, standardize them, sort them. I had been intrigued by the processes of transformation and decay in the environments where I live long before this. Repairs allow me to understand, in microcosm, the larger transformations unfolding and, further, how certain communities participate in these transformations. I also admire—I really admire—the minor gestures that hold things together in states of transition. Why has someone decided to apply this tape in that way? Why have they preserved something that could have been bought anew? These decisions are important; they contain layers of emotion.

Repairing is such a rich and generous practice. I suppose repairs will look different in the future—so will the materials we repair with—but I think I will be reproducing them for the rest of my life.

ZP: There is no shortage of things in need of repair. Repairs sensitize us to the barely-held-togetherness—the precarity—of the world.

HM: Right. The world is barely held together. Sometimes it falls apart; other times the duct tape keeps it in place. I feel this way sometimes myself: I am just barely holding it together. Of course, repair also is tied up with care and maintenance, specific forms of labor that are at once vital and precarious—and demanded of certain kinds of bodies.

“The world is barely held together. Sometimes it falls apart; other times the duct tape keeps it in place. I feel this way sometimes myself: I am just barely holding it together.”

ZP: You insist that in working from these repairs you are not glorifying them. If not reverence, what is the posture, so to speak, of your relationship?

HM: I want to be clear: my interest is in the transformation of objects, not in their destruction. I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. Because repairs are composed of minor gestures, glorifying them would seem out-of-balance. They have to remain in the minor realm. I guess you could say I have a deep interest—an admiration. Admiration itself may be too major for what the repairs themselves would be comfortable with. Deep study might work, too. Again, study is what the process is about: encountering repairs, photographing them, and, finally, getting to know them on the loom.

ZP: You are wary to never exhibit the photographs and weavings alongside each other so as to avoid their indexicality. In fact, you call these photographs “cartoons,” which suggests they are farcical, absurd, unreal—less real, maybe, than the woven reproductions. What is the import of this term: cartoon?

HM: I use cartoon as an art-historical term. In the sixteenth-century, preparatory drawings were made on hard paper or cardboard—hence the name cartoon—before being woven into tapestries. Deeming the photograph a cartoon indicates that it is indispensable to the process but in a strictly utilitarian way. The photograph is a model, a draft, a drawing behind the warp. The weaving cannot happen without it but once the weaving is done, the photograph can be discarded. This is how I stituate photography in my work. It is a support structure.

ZP: On the one hand, you avoid taxonomy by refusing to grant the photographs privileged status. On the other hand, you enumerate all the materials you use with the meticulousness of a taxonomer. For Materials (Arena, Pula), you note: “hand-woven and hand-knit textile and repurposed knitwear (black mercerised cotton, black organic cottolin, black silk, black viscose, turquoise organic cottolin, turquoise silk, yellow mercerised cotton, yellow organic cottolin, repurposed black, dark yellow and grey knitting yarns).“ For another work, also from the Materials series, you list: “Hand-woven textile (white spray-painted bright pink recycled polypropylene, bright pink mercerised cotton, light pink organic cotton, beetroot hand-dyed raw wool, recycled nylon).”

HM: It’s true. [Hana laughs]. The science of taxonomy, classification, and categorization is violent and it has an ugly history to show for it. Any serial practice—my work with repairs, for instance—risks becoming typological. I am interested not in the patterns of repairs but in the singularity of each. Each repair that I reproduce borrows its shape, colors, and textures from the original. It’s positioning, too; the pieces are hung at the height at which they exist in the world. Only infrequently are they located at eye-level.

I am just as invested in the singularity of materials. Weaving has been and remains a way of learning about where certain fibers come from, which production processes they require, who the workers—insects, animals, humans—are that perform these processes, and what trade relationships they are enmeshed with. Describing yarn with utmost precision is an act of respect, I think, even when in doing so one has to admit they are entangled with racial capitalism or slavery. All of the fibers that I have access to are going to be troubled. They will never be innocent. Working with textiles will never be innocent, so I want to be fully transparent about what I know about a yarn. It is the weight of the world that I am participating in.

“All of the fibers that I have access to are going to be troubled. They will never be innocent. Working with textiles will never be innocent, so I want to be fully transparent about what I know about a yarn. It is the weight of the world that I am participating in.”

ZP: Do you use materials that you don’t—or can’t possibly—know about?

HM: Yes, definitely. Even when you can’t deduce the properties of a material, you can learn about it by relating it to those that you do know about. You can also test the material by touching it, rubbing it in certain ways, curling it, heating it up. I like that it is by rubbing something—not some “scientific” procedure—that I am able to understand what it is and where it comes from. The more things are twisted—intertwined—with each other, the more difficult it is to be precise. This is also part of the study.

ZP: In the modern distinction of amateurism from professionalism, the former is defined by passion, contact, and inappropriate proximity, whereas the latter is typified by standardization, “critical distance”—that terrible phrase—and objectivity. Do you think about your intimate study as amateurish?

HM: I most love those things that show me what they are. This is why I love weaving; when you look at a woven fabric you can see how it is made, almost without exception. Weaving is both a magical and demystifying process. I insist that people should be able to detect the way my work is made: where the fibers bind, where the colors connect. I am not interested whatsoever in complicating things for the sake of art; I don’t want to participate in that tradition. That my work demonstrates its made-ness makes me think that you can do it, my neighbor can do it—everyone can bind horizontal and vertical thread together.

ZP: You’ve discussed the epistemology of touch—of wanting to make haptic images and learning about fibers by feeling them. The cardinal rule of any exhibition space is “Do not touch.” To what extent is touch involved in the presentation of your work? And, if not, how do you ensure that the textiles aren’t returned to visual images?

HM: Most often I show my work in museums and galleries where touching is sacrilegious. I do, despite this, occasionally see people sneaking a touch when nobody's looking. I love that; I really love that. I will never be the one to tell them otherwise. Because my works are fragile—I think they take their strength from their fragility; I am not eager to change this—they are not shown in conditions where they can be touched. I am sorry about this. It’s a compromise I have had to accept. I do hope the works evoke hapticality nevertheless. Here again, position helps establish a relationship with the body and disrupt the ocularcentric. If I make a repair of a door handle, it will be shown at the height of a door handle, which better relates to the hand or hip than the eye.

“Most often I show my work in museums and galleries where touching is sacrilegious. I do, despite this, occasionally see people sneaking a touch when nobody's looking. I love that; I really love that. I will never be the one to tell them otherwise.”

ZP: You are, I know, a voracious reader. For your show in early 2021 at La Loge, Brussels, you placed Ursula K. Le Guin’s “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” on stools around the space. Here, in such close proximity, were tapestries derived from the world as it is and writing about a world as it could be. Do you think of your work as speculative—your weaving as world-building?

HM: My work is about what we have to do before we can build new worlds. We need to study what we have before we can speculate, before new worlds can be imagined. We have to take care of what we have before moving on. Worldbuilding is the horizon that I’d like to approach. I just don’t think it is okay to do so yet; there are too many toxic fibers that still need to be woven.

ZP: Each piece takes a long time to make. There is the preparatory work of gathering, processing, and dyeing the materials. You then must fastidiously prepare the loom. And then there are several weeks of physical strain, attempting to move the hulking wooden loom to your will. How do you spend your time while weaving? You’ve suggested, I recall, that you often use it to learn, to study.

HM: When I am setting up the loom, I can’t do anything else. There’s so much math. I count aloud. But, once the loom is prepared and the weaving begins, there is a certain motion in the body that makes me especially receptive to information. I was particularly moved by listening to a series of Audre Lorde lectures on the erotic. Listening to her voice, having her in the room, hearing her discuss the unconstrained power of the female body—it was very poignant. I’ve also recently listened to Beatriz Colomina’s talks on health and architecture.

ZP: Are Lorde or Colomina woven into the pieces you were making while they were in the room?

HM: I suppose. Those pieces are not about Lorde or Colomina but I am sure listening to them did transform the work in subtle ways. It cannot not influence it. It flows into the weave.

ZP: The yarn may have been listening, too.

HM: Many yarns are made of proteins—living materials. They surely have receptive capacities.

ZP: You are exceedingly busy. This year you have two institutional solo exhibitions, including your first at home in Croatia, at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Rijeka. The pace with which you are able to work is constrained by the medium in which you work. Do you experience this slowness as a frustration?

HM: No. The slowness is a refuge, really. That said, having two institutional exhibitions has been difficult. I am still understanding how productive I can be—and how productive I want to be. It is important that I honor weaving’s slowness.

All of the things that I do are very slow. I am a horrible judge of time. I also feel it is the thing I am constantly running out of.

ZP: It is true. We are all running out of time.

HM: It’s a planetary truth, I think.

Hana invites you to read:

The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin

THREAD-TWISTERS: On a Barbarian Loom, Lisa Robertson

Garments Against Women, Anne Boyer