HANNE LIPPARD

ON THE FEMALE VOICE, UNTRANSLATABILITY, AND PIGEONS.—08.03.21

Hanne Lippard (b. 1984, Milton Keynes, UK) is an artist, once call-center agent, and occasional poet. She lives and works in Berlin.

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): You have been very busy this year. Three solo shows: Monaco, Antwerp, Metz. And several more group shows: in Cincinnati, Turin, and Trondheim.

Hanne Lippard: Three? Time is so confusing right now. The Monaco show, Fade-out, was in January, which already feels like last year. Contact Mood Share opened in Antwerp in March and runs through December. In truth, it is three shows—or one show split into three parts. Contact is first, then Mood, and finally Share.

Z You have also released a new album, PigeonPostParis: a “ramblin’, diaristic travelogue” of your stay in the French capital under lockdown. You recount the comings and goings outside your window, “the restlessness of daily life in a small apartment, and the difficulties of understanding, and being understood, when speaking French with a mask on.”

HL Yeah. I spent the lockdown in three cities: Venice, Berlin, and Paris. Venice was completely dormant. Berlin, with all of its open spaces unoccupied, was a void. And Paris just felt like a set. It’s a city with so many clichés. It’s like you are stepping on clichés, and stepping into them: the rude waiter, a man placing Amélie on his harmonica. I began to wonder if I was on The Truman Show, with the municipality paying everyone to occupy just the right place.

“It’s like you are stepping on clichés, and stepping into them: the rude waiter, a man placing Amélie on his harmonica.”

Z PigeonPostParis recalls Georges Perec’s An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, in which he endeavors to record every humdrum detail about Place Saint-Sulpice over three days. He declares: “My intention...[is] to describe that which is generally not taken note of, that which is not noticed, that which has no importance: what happens when nothing happens other than the weather, people, cars, and clouds.” You endeavored to do something similar.

HL An Attempt is all about attention to detail. Perec called this the “infra-ordinary”; I really like that word. I think that perceptiveness becomes even stronger under lockdown, when your movements are restricted to a single kilometer. In a sense, by confining himself to Place Saint-Sulpice, Perec was pre-enacting the conditions I was writing under.

Z And like you, Perec was mesmerized by pigeons; at one point he counts two hundred. Of pigeons, you write, “Their gray feathers weathered and worn as if they’ve been passed through a public digestive system.”

HL Paris has an air of pristineness and high-luxury but is really an awfully dirty place. The pigeons are representative of this; I mean, they are called “flying rats.” There are lots of proper rats in Paris, too.

Z I imagine you at the runoff of this public digestive system, collecting scraps of the infra-ordinary—especially public language like the metro announcer telling you to mind the gap, the receptionist asking you to please hold, the spam bot begging for your company—and reassembling them for us.

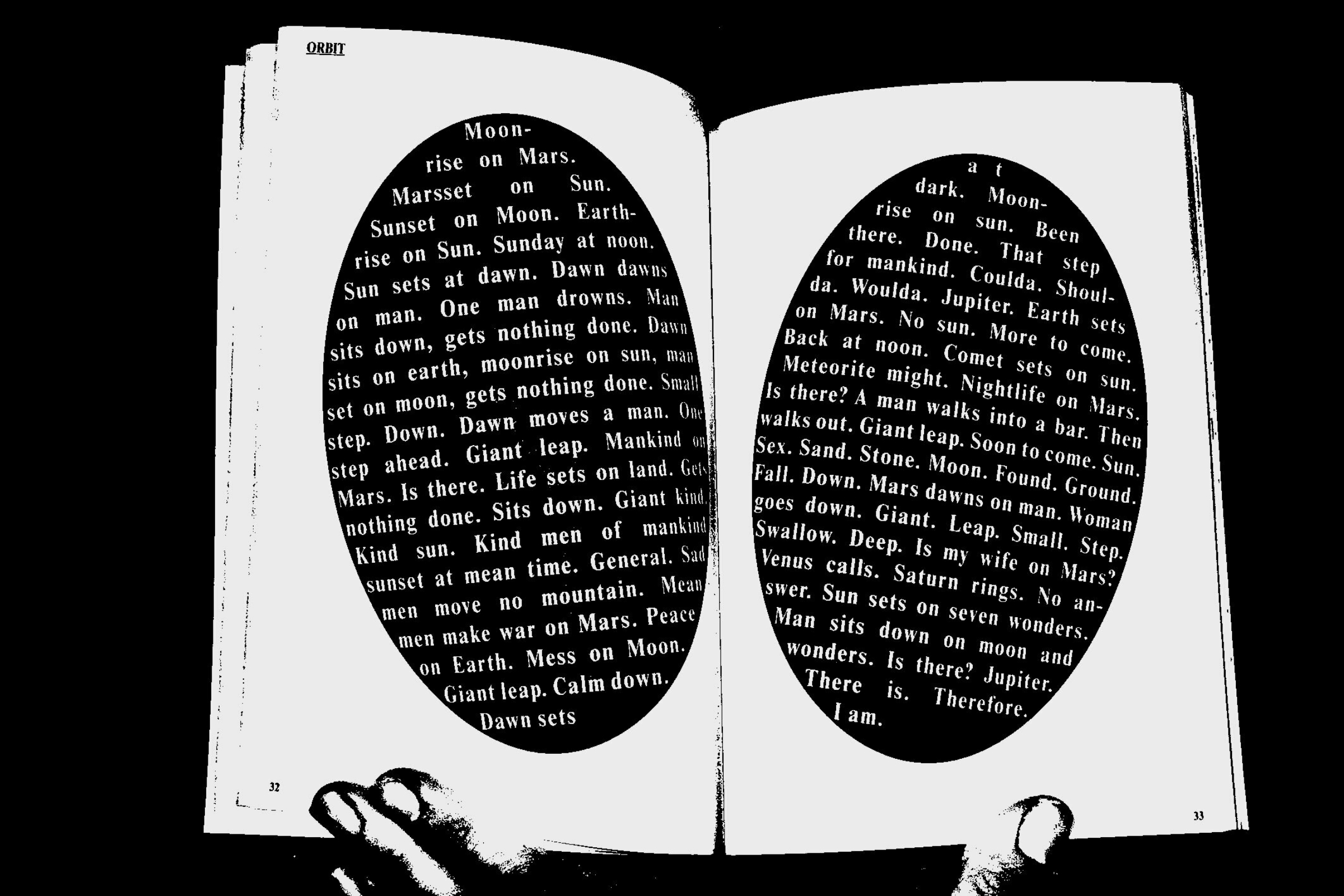

HL If there is something to be collected, I will collect it, then rebuild the language into poetry. I think about these pieces as cutouts—like when you take scissors to a book. So much can be represented by gathering the small traces of society.

Z The residue.

HL Yeah. Lately, I’ve developed a particular fascination for spam emails—the pigeons of writing, you could say. So much of the language we consume today comes from bots.

Z You once worked at a call center, didn’t you?

HL Yes. I was a customer representative for a Swedish company. At the time, I was working as an artist but not being paid much. I was very, very broke, really. I would switch between using my voice for exhibitions and performances and using that same voice for €11 per hour on a support hotline. I wasn’t paid more than anyone else, obviously. I was always thinking, this is my..

“I would switch between using my voice for exhibitions and performances and using that same voice for €11 per hour on a support hotline.”

Z My precious medium.

HL Right. My precious medium. It was very strange. That only lasted a summer. I then became the Norwegian voice for a language-learning app. I am named “Female 1” and the other person is “Male 1.” I would go into a studio and speak Norwegian into a machine for two or three hours. It felt like an alternative reality since I don’t usually speak Norwegian in my daily life, other than calling my mother every other week. I would occasionally have conversations with “Male 1,” but I never saw him. I just heard his voice and would have to respond to his questions.

Z Were you instructed to speak in any way: slowly, enthusiastically, monotonously?

HL Fervently. That’s it. In auditions for other commercial jobs, I was told that my voice had too much personality. They want you to speak quickly without any trace of individuality. Unless you are famous, of course, in which case you have permission to speak as you are. Like Brad Pitt reciting poetry in that Chanel ad.

Anyway, speaking to a faceless Norwegian body as a faceless Norwegian body was some experience. Eventually, I began to make a living off of my artwork and could stop doing the odd jobs. Between the call center and the app, I was thinking a lot about the voice and anonymity. My first solo show was during this period, at Kinderhook & Caracas, a small, little space in Berlin run by two friends of mine, Sol Calero and Chris Kline. It was about the spirit of the Oracle of Delphi being stuck in a call center. As the legend goes, the gods spoke through the Oracle of Delphi. Male priests would transcribe her jabberwocky and make reason out of it. As a woman, she was presumed to be nonsensical so the men had to render her intelligible.

Z Be it “Female 1” or the Oracle of Delphi, you have always been attuned to the expectations of and demands on the female voice—the way that gender mediates semiosis. In Frames you ask, “Can a voice be sexless?”

HL It’s true. I’ve recently been thinking and writing about bots. Siri, Alexa, Echo—they are all women. Proper women. They never burp or growl. They reply kindly to rude questions.

Our word “echo” derives from a tragic Greek myth about a woman who, after sleeping with Zeus, is cursed to only repeat the words of others. She ends up falling in love with Narcissus—which is a very bad choice.

“Siri, Alexa, Echo—they are all women. Proper women. They never burp or growl. They reply kindly to rude questions.”

Z Thank you for that clarification.

HL She should have swiped left on Tinder. Narcissus rejects her and she is so heartbroken that she cries until her body becomes nothing but stone, reflecting the words of others. A body completely devoid of integrity. She neither has her own voice nor body in the end.

Z Alongside your other compositional techniques—rhyming (Numb Limb, New Empires, Old Vampires), homonyms (“T’aime” and “Time”), alliteration (PigeonPostParis)—you often employ echoing, taking fragments of language and repeating them back to us until they dissolve into sound.

HL Yes, absolutely. When I was studying graphic design, I did a lot of work with repetition in typography. I think it comes from that. But I find that when sound is repeated, it is much more invasive—it invades the listener’s ears.

Z Do you know Bruce Naumann’s video work Good Boy, Bad Boy? Two actors—they’re also named “Male” and “Female”—repeat the same hundred sentences ad nauseam, with a different intonation each time. “I am boring. You are boring. We are boring. This is boredom.” First giddy, then aggrieved, then melancholy, then distracted.

HL I do. It’s an interesting piece. It tests who you give more authority: the man or the woman. When I was doing research for my upcoming show in Metz, there happened to be a conference on the female voice. I learned that female voices are perceived to be more credible than male voices for information—announcing the bus stop, let’s say—but less effective in giving commands.

I also like the way that with enough repetition, speech becomes just a blob of sounds.

Z Speaking of which, you make use of several languages: English, French, Norwegian, Swedish, German. You’ve said that “When I use the non-English languages, I use them more as sounds.

HL In a sense. That approach has been challenged recently as I work in more non-English speaking countries. For an upcoming exhibition, I am making a sound piece which they’ve asked that I also read in French. Some things just cannot be translated. I adjusted a few works for the show in Antwerp because they required some Dutch and French understanding. I noticed that a lot of it got lost. It was impossible to retain the duality of certain words. The aphorisms and word-plays just failed.

Z One would never suggest that a painting be translated.

HL I know! I get a bit provoked. It is a battle I’m fighting: the flexibility of my own work and its language. People get confused about it, even curators who have been working for a long time. They imagine it is always translatable—that I could possibly speak it in other languages that I am not fluent in.

There is also a confusion that my work can be placed anywhere—the passages and the dead-ends, the toilets—or be complementary to anything. I don’t want it to be a press release.

“There is also a confusion that my work can be placed anywhere—the passages and the dead-ends, the toilets—or be complementary to anything.”

Z This tends to happen with sound, because of its perceived immateriality, I think. Sound art can become no more than muzak.

HL Yes. Art muzak. It’s almost like hotel art.

Z Tell me about the sound art market. I don’t imagine that private collectors have your pieces looping in their living rooms.

HL I’m curious about this as well. I haven’t really asked a collector, but I doubt they play me constantly in their own home. I have only sold works to private collectors in France, and a few in Germany. It is not very common. It seems collectors are after squares, tangible squares. I haven’t made so many squares.

“It seems collectors are after squares, tangible squares. I haven’t made so many squares.”

HANNE INVITES YOU TO READ:

- Break.Up, Johanna Walsh

- A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments, Roland Barthes

- Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word, Walter Ong

- “Gender of Sound” (from Glass, Irony, and God), Anne Carson