GABRIEL KURI

ON PRESENCE, SKATEBOARDING, AND ATTENDING THE EVERYDAY. — 06.22.20

Gabriel Kuri (b. 1970, Mexico City, Mexico) is “a selector”—and once rock drummer. He joined Gabriel Orozco’s workshop Taller de los viernes from 1987 to 1991, received his BA in Visual Arts at Escuela Nacional de Artes Plásticas in Mexico City in 1992, and completed his MFA at Goldsmiths University of London in 1995.

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): I spent yesterday listening to Fobia, the nineties Mexican rock band. You were Fobia’s founding drummer, I understand.

Gabriel Kuri: That’s correct. Paco Huidobro, the guitarist, and I met in high school. We started Fobia with two other kids from a neighboring academy. We carried our instruments here and there around Mexico City, played in small clubs and at house parties and all sorts of shitty and unlikely events. With time, we went on to make our first album, Fobia, did a bit of touring, and then made a second, Mundo Feliz, and a third, Leche.

All the while, I was enrolled in art school. When I finished my bachelors and left Mexico City to study in London, I committed myself to visual art. I left the band. No one could understand why I would do that; we had a contract on the table for three more records. I gave up my royalties and quit.

Drumming and rhythm are still with me every day. I’ve never included music in my visual work, perhaps out of fear of these two worlds mixing again. But maybe one day.

Z: Do you listen to music in the studio?

GK: I need music in the background to work. It becomes a landscape that I occupy. That landscape changes. Recently, I’ve found myself playing more and more instrumental music. For a long time, I couldn’t stop playing Horse Lords, an avant-garde rock band from Baltimore. I’d like to make music like theirs: the rhythm—the broken rhythm—the structure, the math, the energy, the texture.

“I’D LIKE TO MAKE MUSIC LIKE THEIRS: THE RHYTHM—THE BROKEN RHYTHM—THE STRUCTURE, THE MATH, THE ENERGY, THE TEXTURE.”

Z: Are you as interested in found sound as you are found objects?

GK: In truth, when I look for sonic stimulus it is from music not from bits of sound. I’m hesitant about the passive acceptance of a certain kind of musical composition—sourced from the incidental—that is justified in its reference to the Duchampian idea of readymade or the Cagean idea of indeterminacy. Too often this strategy is used as license to avoid the hard work of composition, to just pick things because that’s what Marcel Duchamp or John Cage would have done.

I have to admit, as a visual artist, there is a certain snobbery in our milieu assuming that we can make better music than musicians can make visual art. I am thinking, for instance, of the unsurprising paintings of Bob Dylan, David Bowie, or Leonard Cohen. The reasons why would involve a much lengthier conversation (while we listen to great bands that formed in art school, maybe).

Z: Your visual art practice emerged alongside your drumming. José Esteban Muñoz, the late performance studies scholar, contends that (punk) rock “aesthetics tell us the story of the negative.” I see the story of the negative in your work.

GK: I think of my work not as oppositional—in the way that punk is often discussed—but as affirmative. I see possibility in the marginal and overlooked. I do not intend this to be egoist; I do not intend to say that I can see art in this while you cannot. Rather, I can see this and maybe so can you.

“I SEE POSSIBILITY IN THE MARGINAL AND OVERLOOKED. I DO NOT INTEND THIS TO BE EGOIST; I DO NOT INTEND TO SAY THAT I CAN SEE ART IN THIS WHILE YOU CANNOT. RATHER, I CAN SEE THIS AND MAYBE SO CAN YOU.”

Z: One of your earliest works Doy Fe (1998) is a sculpture of a fried pork-fat snack into which you engraved “by my will,” a phrase said at the end of a religious ceremony to consecrate an object or body. This affirmation recalls poet Mary Oliver’s words, “Attention is the beginning of devotion.”

GK: I like that. Doy Fe is, indeed, all about awareness. Before that humble snack you become aware of your own existence because you are looking at something that is looking back at you— returning your gaze. It is about that space between you and something else by which you mutually acknowledge your existence and co-presence.

Z: Animism, perhaps?

GK: I don’t ascribe souls to artifacts but I do, of course, feel that there is a mysterious force latent in art objects. That is ultimately what I look for and aspire to produce. It is quite ambitious to think that one can make something—with plastic or paper, any material, really—that will have a life of its own. If you want to call that animism, I’m fine with that.

The anima calls to mind the aura; I still believe in the aura. I was recently asked about the best online exhibition I’ve seen. That question struck me. Exhibition and virtuality are difficult to reconcile. In the time that we are quarantined, I would rather focus on my longing to be present again than to accept online exhibitions as a satisfying surrogate. Sure, viewing a .jpeg of a sculpture may be exciting, but what gives that sculpture its symbolic and social power is something in its presence. Art should be a resistance to life online.

“IN THE TIME THAT WE ARE QUARANTINED, I WOULD RATHER FOCUS ON MY LONGING TO BE PRESENT AGAIN THAN TO ACCEPT ONLINE EXHIBITIONS AS A SATISFYING SURROGATE. SURE, VIEWING A .JPEG OF A SCULPTURE MAY BE EXCITING, BUT WHAT GIVES THAT SCULPTURE ITS SYMBOLIC AND SOCIAL POWER IS SOMETHING IN ITS PRESENCE. ART SHOULD BE A RESISTANCE TO LIFE ONLINE.”

Z: Some have celebrated the accessibility of online exhibitions. Writing in ArtReview, Ben Eastham says: “I like experiencing art at home... It is democratic: I don’t go to the Tate because I like peering through crowds of people to see a Matisse that was intended to decorate a drawing room, I go there because I don’t have a Matisse or a drawing room in which to hang it. It relieves art of at least some of the barriers of class and inherited taste that protect it.”

GK: That’s too easy an argument. I think it is insubstantial. The aura demands you be there. And if you don’t have to be there, then I don’t think you should so easily claim the pay-off. I believe that art can be really life changing; I know it changed my life. And those life changing encounters would have been impossible if mediated. They were made possible by presence.

Z: Did you skateboard as you were growing up in Mexico City?

GK: I did. When I was seven or eight years old the first wave of skateboarding culture came from the United States to Mexico with Stacy Peralta, Tony Alva, and Jay Adams. I picked up a skateboard then but I couldn’t do much. I was too young.

Z: I sense a skaterly perspective in your work. Skaters reconfigure the city into a playground; curbs, handrails, ledges, hydrants, planters, and benches become their materials. .)(. (2013), items in care of items (2008) and Broken line 1 (2013) even resemble make-shift ramps and rails.

GK: It’s true. The skateboard is an instrument to explore the city’s surfaces and contours. I often make work from that perspective, like Untitled (Ticket Roll), a sculpture of three black marble slabs with parking tickets threaded through the crevices. I made that piece to articulate the bodily experience of parking my car. It was an attempt to conjure the motions involved—reversing, curving. Likewise, when you are skating you are looking for forms and materials: straights, surfaces, ledges, all that. It is an embodied way of being in the city.

I’ve always been fascinated by the buildings that skaters gather around. It says a lot about the period in which those buildings were made. Skaters congregate around the Southbank Centre in London because its Brutalist forms are perfect for skating. Meanwhile other buildings—particularly older buildings—are inhospitable to skaters.

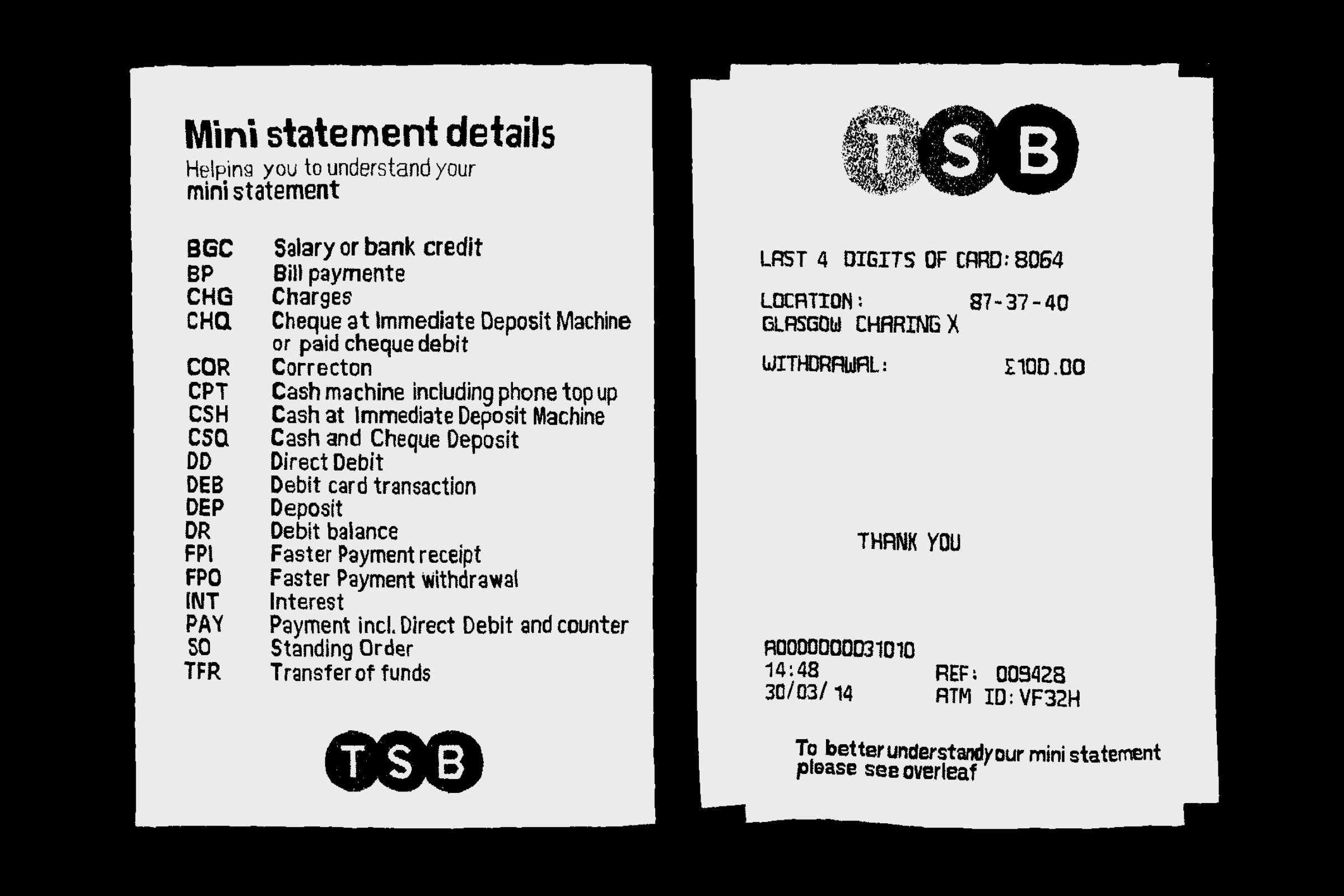

Z: Many of the materials that you attend to, like the ticket roll, are texts: receipts, newspapers, adverts, lottery billets, fruit stickers. Are these linguistic readymades?

GK: I’d call them administrative readymades. I am interested in official, bureaucratic language, and in trying to see it for more than how it functions. I am of course also interested in the linguistic readymade. I have been an Ed Ruscha devotee my entire life. I think he is one of the great living artists. The way he has used linguistic readymades is a source of endless inspiration for me.

Z: The “administrative readymade” reminds me of something you published in the New Yorker. “Seventeen syllables is a haiku. “Eighteen syllables is an unauthorized withdrawal of company resources and will be punished to the fullest extent of the law.” The difference between poetry and bureaucracy is one syllable.

GK: Exactly.

Z: Your use of language as material—and in refusal of its signification, aboutness—evokes the project of the New York School and Language poets.

GK: They haven’t influenced my work, at least as far as I am aware. I love reading and I love poetry; I read as much as I can, which never feels like enough. But the sources for my visual art are rarely literary. I don’t read a book and make art about it, neither do I research something on Wikipedia and make art about that. My art comes from firsthand experience.

Z: Gabriel Orozco did call you a “poetical activist.” What did he mean?

GK: That was 1998. At the time I was much more interested in words. I was making paintings with words. I was distributing printouts of poems that I had collected from certain authors and illustrated myself. He found them wacky. “Poetical activist.” Who knows what he meant?

Z: You have published several catalogues and artists’ books: join the dots and make a point (2011), All Probability Resolves into Form (2014), Before Contingency After The Fact (2015), With Personal Thanks to Their Contractual Thingness (2015), and Sorted, Resorted (2019). Do you treat books as sculptural objects?

GK: Of course, though sometimes more than others. For All Probability Resolves into Form, my 2014 show at The Common Guild in Glasgow, I envisioned an artists’ book that was intended to guide viewers through the exhibition. That is strictly an artists’ book; the content of the book does not exist elsewhere as an artwork, though I sourced the images of polling stations and disaster shelters therein from the Associated Press. It is not always possible to make books with such freedom and independence, however. Even in the case of traditional catalogs, I am very involved. I want them to be as unconventional as possible and to have a life beyond the show. I obsess over the layout, the choice of paper, the titles—everything.

I have learned a lot from working with publishers, like Christophe Boutin and Melanie Scarciglia of onestar press. Christophe always told me not to make catalogs, to not call designers, to do everything myself. That is an amazing piece of advice, though not always a feasible one. But it’s an ethos I’ve carried along when making books that serve an institutional or art historical purpose.

“CHRISTOPHE ALWAYS TOLD ME NOT TO MAKE CATALOGS, TO NOT CALL DESIGNERS, TO DO EVERYTHING MYSELF. THAT IS AN AMAZING PIECE OF ADVICE, THOUGH NOT ALWAYS A FEASIBLE ONE. BUT IT’S AN ETHOS I’VE CARRIED ALONG WHEN MAKING BOOKS THAT SERVE AN INSTITUTIONAL OR ART HISTORICAL PURPOSE.”

Z: You designed a series of bookshelves for onestar in 2012. How did this come about?

GK: I’m restoring them right now, in fact. onestar commissioned a series of bookshelves by artists— Annika Ström, Lawrence Weiner—and asked me to participate. They instructed me to make a bookshelf that would accommodate a certain collection of books. That was the only limitation. So I set out to make a bookshelf that was both sculptural and functional.

Z: What is on your bookshelf right now?

GK: I have been reading Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects. It’s a treat. At its most basic, it is about how history has been written with objects—often in a more accurate way than with text. I also bought myself a father’s day present this year: Joseph Beuys’ Drawings After the Codices Madrid of Leonardo da Vinci. It arrived in the mail today. The drawings are sublime.

GABRIEL INVITES YOU TO READ:

- The Shallows, Nicholas Carr (the most enlightening book about what the internet is doing to our brains.)

- La Escuela Del Aburrimiento, Luigi Amara (or anything by the essayist/poet. In Spanish only, perdón.)

- How To Do Things With Words, J.L. Austin

- How To Do Things With Art, Dorothea von Hantelmann