JILL MAGID

ON QUESTIONS, FICTION, AND BECOMING A DIAMOND. — 06.04 / 11.12.20

Jill Magid (b. 1973, Bridgeport, CT, USA) is a conceptual artist and writer. Her work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at Tate Modern, London; Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; San Francisco Art Institute; and the Stedelijk Museum Bureau, Amsterdam, among others.

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): The Renaissance philosopher Montaigne called his writings “essays” — “attempts” (from the French essayer, “to try”). In English, essay first meant “a legal trial.” You have said that your work begins when “I’m curious about a system and pose a question to it.” Do you see your artworks as essays?

Jill Magid: Yes and no. Yes: I like thinking of my artworks as trials, with an emphasis on “trying.” They are hypotheses. I never set out to argue a point; that is too easy. Rather, I attempt to explore something to the point of exhaustion—to ask it questions, to get to know it most intimately. Critics who view my work in terms of its answers are always frustrated.

“CRITICS WHO VIEW MY WORK IN TERMS OF ITS ANSWERS ARE ALWAYS FRUSTRATED.”

But no: to suggest that my works are essays would be to reduce the particularities of the mediums I use. It is important to me that the form of what I make succeeds on its own terms, and couldn’t be said just as well with words on the page.

Z: You have worked in just about every medium. How do you find the right form for the question?

JM: That has become more and more challenging. With Evidence Locker (2004), one of my first epic projects, the medium was decided for me. The Liverpool Police department recorded CCTV video, kept it in real-time for the first twenty-four hours, thereafter turned it to three-frames-per-second, and deleted it after three days. To access the footage I had to fill out a Subject Access Request Form. The media—film and letters—were mandated by the system. That was a total gift. I enjoy when the system gives me a base vocabulary, which I can then push as far as I’d like. I am a huge fan of the default. I really hate arbitrary decisions.

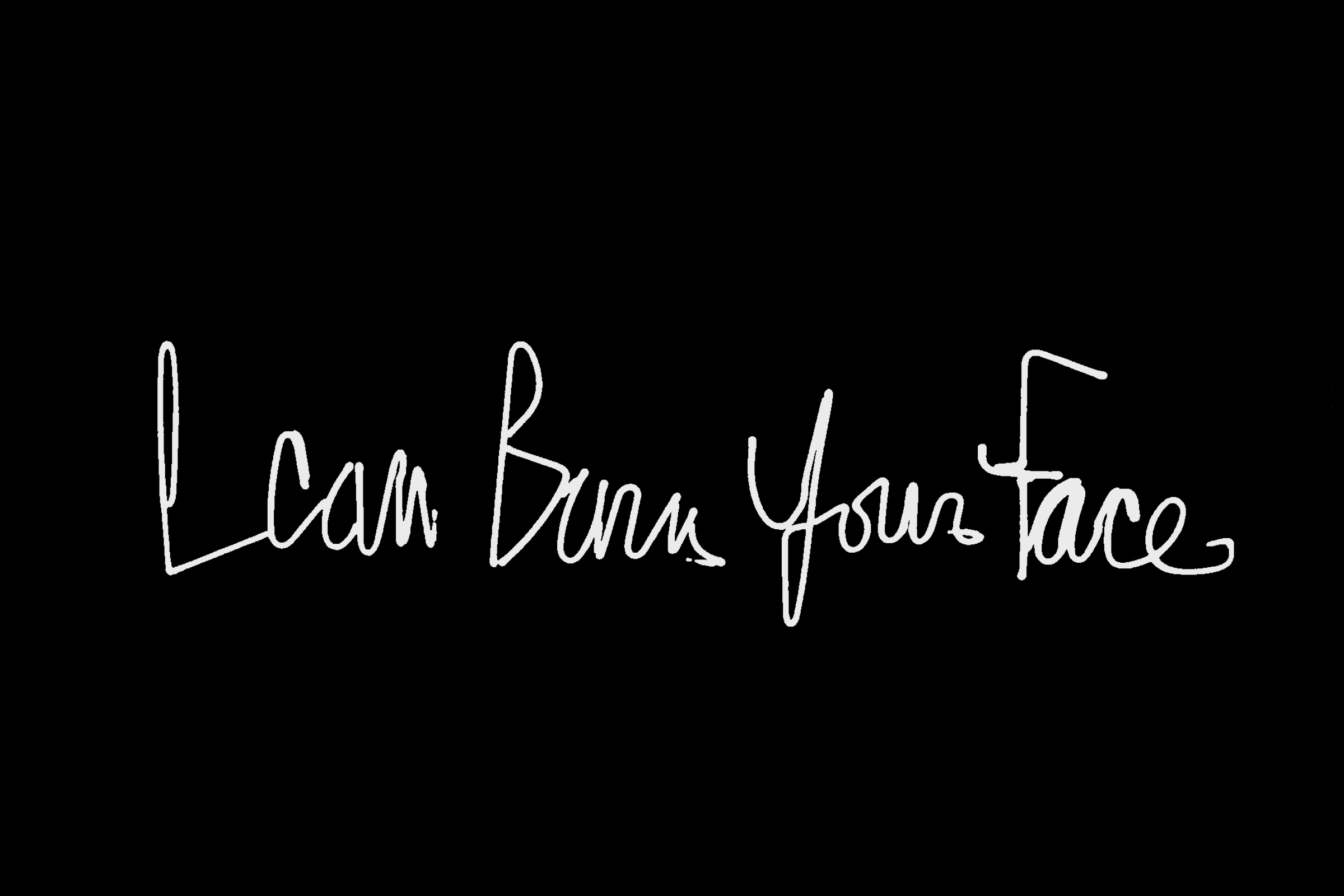

The Spy Project (2005) was different. The Dutch General Intelligence and Security Service (AIVD) said that I could interview their agents but only record them with pen and paper. I proposed to write a book, in turn. But it was difficult to capture the spirit of my conversations with the agents, and I felt incapacitated for a while in the writing. Each agent used a different kind of mask: some of them would talk themselves up in a clearly over-exaggerated way, others seemed to be flat-out lying, and yet others told me more than they probably should have, using me to be able to voice what they otherwise couldn’t. There were some ways that they spoke that lent themselves to formal applications. For instance, the agents kept saying that I could “burn them.” I wanted to use that language of “burning” someone’s identity literally, so that my descriptions of the agents were actually burning. My original idea was to use the kind of wires in a radiator or old space heater that burn orange when hot.

Z: To which the museum said...

JM: Nice try. I had to use neon. And of course neon has its own history—its own competing vocabulary, which I had to navigate carefully. The diameter of the neon I chose is extremely small; the smaller the diameter, the more ferocious the light. It filled the room with a buzz. Interestingly enough, when I showed the neon so many viewers remarked that they’d enjoyed that I heated the room. That was all psychological. There was no temperature shift. People said it enough that we actually tested it.

A lot of times I find the form through a slippage of language—the idea of burning, for example. Language helps me arrive at formal solutions.

“A LOT OF TIMES I FIND THE FORM THROUGH A SLIPPAGE OF LANGUAGE—THE IDEA OF BURNING, FOR EXAMPLE. LANGUAGE HELPS ME ARRIVE AT FORMAL SOLUTIONS.”

Z: Becoming Tarden, your book from The Spy Project, was published in redacted form after the AIVD confiscated the uncensored manuscript. Did the censorship feel appropriate to the way you were communicating with those agents?

JM: I never thought of it like that, or at least not initially. After receiving the redactions, I was devastated. I felt like I’d been robbed of my novel. It took a while to recognize what their censorship gave to the project rather than what it took away from it. And I realized that the redactions mirrored the larger system of control, even exposed it. The director of the intelligence agency made those decisions. It was his voice that was being reflected.

Z: Is he a co-author, then?

JM: In a sense. That’s what I came to love about the redactions. Unlike Evidence Locker where the presence of the police officers is integral to the work, in The Spy Project the agents become present through their absence. Everything else was my perception. When I first learned that the book was being censored, I thought they would take out a phrase or word here and there. And then they removed forty percent.

I have wondered what it would say to deem them co-authors. It’s a good question: is censorship authorship? I almost feel that in a political sense it gives too much power to call the censor an author. I would, though, absolutely say that the act of censorship changes the meaning of the work.

Z: “Permission is a material,” you’ve noted.

JM: “...and changes the work’s consistency.” I strongly believe that.

Z: In Where Do Characters Go When the Novel Ends?, Dora García writes that “A good question should at all costs avoid getting an answer.” Do you agree?

JM: I believe that a good question explodes into a million nuanced ones. Finding the right question is the hardest part of my work. I imagine it like a sculptor whittling down a log into a fine yad—those Jewish pointers used for reading the Torah.

“I BELIEVE THAT A GOOD QUESTION EXPLODES INTO A MILLION NUANCED ONES. FINDING THE RIGHT QUESTION IS THE HARDEST PART OF MY WORK.”

Each project begins by figuring out what the question is, and how to ask it so that it can be heard. To arrive at the right question, I have to build up a new vocabulary that makes sense in relation to the vocabulary of the system. For instance, in Woman with Sombrero (2013–15), the first chapter of The Barragán Archives, the question is about representation: how do you represent something that is illegal to represent? I had to come up with a whole formal language that sculpturally poses that question. It took a long time to find those forms. It took a really long time.

I am admittedly jealous of those artists who build a vocabulary and have their whole lifetime to enrich it. While there are things that carry from one project to another, I usually don’t recognize those overlaps until after the fact. It feels like each time I am starting anew.

Z: Your latest project, Tender, is a “diffuse monument” of 120,000 pennies. On each you have engraved “The Body Was Already So Fragile.” What questions begot this project? What does it ask?

JM: When considering the commission from Creative Time—to make a public artwork in New York—I knew I had to begin where I so often end: at a question that gets asked loudly, sometimes spectacularly. To begin at that scale, rather than to arrive at it through the work itself, was daunting to me, especially during the pandemic. Over the last several months, I have been asked again and again, Why is art important now? And so, I began to consider what a monument for this moment might be. I was after a public artwork that wasn’t sited, that you could not go visit, but that came to you: that actually got used, held, and spread by the public.

Tender is a vast project, made up of thousands of coins, yet it can only be experienced on an intimate scale: you find one penny in your hand; at most, a bodega owner might have a roll. Tender consists of 120,000 pennies but the sculpture is also each individual penny. That’s important. It reflects the real difficulty of making sense of the fact that this immense death toll represents so many individual lives. How can a memorial grasp the massive scale of this global catastrophe without losing hold of the scale of each irreducible loss?

I wanted to ask what the functions and forms of public art can be. What are its limitations and what are its possibilities? Can an artwork bridge the personal and the structural? The “Body” refers both to the single human body and economy as a body, raising questions about how one puts pressure on the other.

Z: You describe pennies as a “small, promiscuous” monuments. Social psychologist Michael Billig calls them “banal nationalism.”

JM: It sounds like Billig and I agree. The images and texts on a penny are so ubiquitous as to be invisible: the Lincoln head and the Union Shield—symbolizing a single, united union—are so frequently reproduced and appropriated that they have been flattened. What is this idea of a united union, especially now in our divided nation? Incising an elegiac phrase on the smooth edge of the coin, for me, triggers a kind of double back, a snare in the system (of the penny as circulating, legal tender) that makes the reader of its message trip up and reconsider the coin—and the system in which it circulates. The penny is the most unvalued of coins; they dot sidewalks, few caring to pick them up. What is it to mark this coin that on its own is hardly able to pay for anything? What is it for this little object that has almost become worthless to be the bearer of a message like this? The whole national tragedy on some level has unfolded as people make decisions—active but often unspoken—about who or what has value and, in turn, who can be ignored.

Z: You insist that artworks “challenge their viewers.” But you too seem interested in being challenged by them—”of creating a conflict within myself,” putting yourself on trial.

JM: If I don’t feel uncomfortable with a work, something is wrong. In truth, I’ve never made a work that I’ve put into the world where I didn’t feel uncomfortable during the process of making it; I would have just put it away. It’s that feeling of being challenged back that drives me forward to explore it. Even when I am looking at other people’s work, I am most interested when it pisses me off. I was just reading Jacques Derrida’s Counterfeit Money. For the first fifty pages I was complaining; I was so mad at Derrida! And then I gave into it, into his logic, and the world he was creating with it. I ended up loving the book. It was like one of those bad sitcoms where the couple fights and ends up sleeping together.

“IF I DON’T FEEL UNCOMFORTABLE WITH A WORK, SOMETHING IS WRONG.”

Z: Discomfort is passionate.

JM: Yes. If you are not uncomfortable with or challenged by something, then why dedicate any time to it? If you are satisfied, just leave it. I only move on once I’ve exhausted the formal and intellectual questions.

Z: Your work is often described as “poetic.” For instance, Chrissy Isles, curator at the Whitney, observes that “Magid’s work is incisive in her poetic questioning of the ethics of human behavior and the hidden political structures of society.” Early in your career you worked for the poet Frederick Seidel. How did you come to work for Seidel, and how did he influence your “poetics”?

JM: I was a devoted writer from a very young age. As an undergraduate I considered majoring in poetry—although I was more interested in prose narrative, I just didn’t know to call it that. One day I happened to receive a call from a friend whose grandfather was friends with Fred. Fred needed someone to do research for him, specifically for a poetry book commissioned by the Museum of Natural History Planetarium. I met him and immediately thought he was fantastic. I researched for that publication and for Ooga-Booga, his book about motorcycles.

I would come to him now and again to report my research. He would first ask me about what I learned and sit patiently as I reviewed my findings. Whenever I would say things like “You know what I mean,” he would wait for me to stop and say, “No, I have no idea what you mean. You need to use your words to tell me.” He was that kind of exacting personality. With time he came to ask me uncomfortable questions—questions for which I had no answers. It was a sort of game that we played. He would wait for me to find the right words until I made myself very clear. He would always tell me not to apologize for anything I felt.

“WHENEVER I WOULD SAY THINGS LIKE ‘YOU KNOW WHAT I MEAN,’ HE WOULD WAIT FOR ME TO STOP AND SAY, ‘NO, I HAVE NO IDEA WHAT YOU MEAN. YOU NEED TO USE YOUR WORDS TO TELL ME.’””

He would also tell me stories in exchange. I could never tell if he was lying or not, but the validity of his words didn’t matter to me. I never felt that he was writing to be popular or make best friends; he was writing to interrogate the world and what he felt. He once told me that there was a period of his life where he didn’t write for a long time. I asked how he handled that, knowing how horribly painful it is when I don’t know what to say or make. He said he was silent because he felt silence. I thought it was brave of him to not need to fill a void when he didn’t know how.

Z: Speaking of not knowing—or caring—if Seidel’s stories were true, you call your books “novellas.” Are they fictional?

JM: This is complicated. It is hard to know what to call my writing. It is non-fiction, you know—wait, not you know! I don’t make up scenes. However, my writing doesn’t try to be objective, though it is strongly observational. I think it is very important that unlike a traditional journalist who doesn’t participate in what they are documenting, I am not only participating, but completely driving the narrative. In fact, the narrative would not have existed if I hadn’t stepped into a system and tried to push its boundaries. So while I am in this very active role, I am also writing about what I am thinking, what I am doing, and how I am perceiving the response. It is non-fiction, but I am creating the story by living it. That zone—occupied by Maggie Nelson, Eileen Myles at times—allows active participation and observation. It is a hard form to define. The reason I like the term “novella” is because of that poetic flexibility.

What I write is true, however. It is all true. And I insist on that truth because there is value in my exploration of these systems. They each behave in particular ways that reveal their missions, or how the underlying laws are written, or how they are performed. That’s why I don’t want to fictionalize. The questions that I’m asking wouldn’t have the same resonance if they were fabricated.

Z: Lord Byron famously wrote that “truth is always strange; stranger than fiction.”

JM: That is one-hundred-percent true. Life would be a lot easier for me if I were a fiction writer and I could imagine these ideas. So much of my work is waiting for the reaction or next move from the other. I can’t control those. It can be really painful.

Z: Given your work with archives—personal, professional, governmental—and efforts to make accessible their contents, how do you archive your work? What instructions will you provide (or have you provided) to your inheritors?

JM: I’m still working out those questions. One of the biggest shortcomings of my art school experience was that nobody taught me how to run a studio or archive my own work. For a long time I had no system. I would just make really messy folders for each project. To this day, my collaborators tease me when I send them files named “final.version124.” When I won the Calder Prize in 2017, I made the commitment to hire someone who could help me organize it all. We have started archiving the projects and pieces. It is very satisfying.

Auto Portrait Pending (2005), in which I signed a contract to have my ashes processed into a diamond, addresses all of this explicitly. With it, I contemplated my body versus my body of work, and the moment the two collapse. I almost felt that after I made that piece it was hard to do any other piece that would ask questions of my own legacy. It is important to me that my archive is collected in a neat, beautiful form and that historically the work is there to be looked at and shared. Like I said of working with Luis Barragán’s archive, the biggest complement of any artist’s work is that people keep it alive by reshowing it and referencing it, or becoming critical of it.

I hope that my work will have a life after me. I also understand that I can’t control that. The least I can do is clean it up a bit. I also would like my books to exist in the literary world as much as in the artworld. I have a problem with the term “artist’s writing.” When I am writing, I care about the writing as literature. Even when penning a contract or a letter, I am thinking of it in literary terms. I want to be held up against writers, not artists who suddenly decided to use words as a medium.

Z: Have you told your children that, one day, their mother will become a diamond?

JM: Yes. My husband jokes that he will become the pair of earrings to accompany it. My older son has said he will buy it one day. I told him that he is absolutely not allowed. It has to have a life separate. In a way, I considered this in the contract of Auto Portrait Pending [Banks, age six, interrupts]—

Z: How appropriate.

JM: Banks knows, but it’s a big thing to get your head around at his age. I believe he and Linus will understand that piece eventually, whether they like it or not. I made Auto Portrait Pending before I had kids, but I had many conversations with my parents about it. It bothered them. They said that they could get beyond the cremation, though it is forbidden in Jewish law. They insisted there be a place to visit. So in the contract I split the ashes. Only the amount of ashes required to harvest carbon for the diamond will be taken and the rest will be brought to a burial site and have nothing to do with art.

That work forced me to really think about death and art and the body and form.

Z: In more than abstract terms.

JM: In very real terms. I don’t know if I would have confronted death in the same way than when I had to think about myself as a body that would become an art object. That is the kind of challenge I want to face from an artwork. What more can you ask from artwork?

“THAT IS THE KIND OF CHALLENGE I WANT TO FACE FROM AN ARTWORK. WHAT MORE CAN YOU ASK FROM ARTWORK?”

JILL INVITES YOU TO READ:

- Cockpit, Jerzy Kosinski

- The The Emperor: Downfall of an Autocrat, Ryszard Kapuściński

- Outline Trilogy, Rachel Cusk