LUCAS BLALOCK

ON AMUSEMENT PARKS, TORTURE, AND MAKING PHOTOGRAPHS LOOK THE WAY THE WORLD FEELS. — 04.13.2020

Lucas Blalock (b. 1978, Asheville, North Carolina, USA) is an artist. He lives and works in New York.

![]()

![]()

$75

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): The last time we spoke you told me a story about a fateful incident at an amusement park. Can you recount this for our readers, in abstract?

Lucas Blalock: For that we need to return to 1989. I am ten years old. My parents take me on vacation. I lose my thumb on one of the rides. We are unable to find it—and, to my knowledge, it remains missing. In a frenzy, my parents phone a doctor-friend of theirs, who tells them of an experimental surgery: there is an option to remove the great toe from my right foot, freeze it, and transplant it to my hand. And that is what we did.

The ghost of my thumb is likely somewhere at that amusement park, lurking like an alligator in a New York subway.

“THE GHOST OF MY THUMB IS LIKELY SOMEWHERE AT THAT AMUSEMENT PARK, LURKING LIKE AN ALLIGATOR IN A NEW YORK SUBWAY.”

Z: If, as Karal Ann Marling suggests, the amusement park is designed as an “architecture of reassurance,” your accident must have made it an architecture of horror. Is this the first time “the apparatus,” to use a term you often cite, revealed itself?

LB: That event was a watershed. Trauma was born out of its opposite, in a rather extraordinary way. The amusement park is a spectacular space in the most literal sense. It’s a place that is an event, a place that doesn’t have a behind the scenes, and in which our bodies become less real. My experience punctured that illusion: not only did the amusement park have a behind the scenes, so did I. I was all of the sudden aware of myself as a body made of working parts that could be damaged.

As a teenager, I became interested in counterculture and, with that, suspicious of idealizations. Did my incident catalyze these suspicions or would they have presented without it? That I’m not sure.

Z: When the Whitney asked you to share a “moodboard” for your work at the 2019 Biennial, you offered a meme: “Fun fact: the internet was once a fun place for watching cat videos instead of monitoring the real-time collapse of late-stage capitalism.” What ideological work does your refusal of “grooming the image” do?

LB: When I started working with Photoshop in 2008, photography felt very intact. People had been manipulating photographic images for as long as there have been photographic images, but there was still a sense that photography had stable boundaries. An image was either a photograph or not. Amidst these conditions, the ideological work of my manipulations was more pronounced. It was a place to throw some sand in those gears, to gum it up a little bit. There was joy and music and strangeness to be made out of playing those games and working against a status quo.

“THERE WAS JOY AND MUSIC AND STRANGENESS TO BE MADE OUT OF PLAYING THOSE GAMES AND WORKING AGAINST A STATUS QUO.”

Now we have such a porous image universe; it is hard to say what a photograph should do. Everybody can change a picture in the way that only professionals were capable of. It feels now more like working in an everyday language of intervention. But I am continuing to ask myself about the limit of what might be smuggled into photography.

Z: Chuck Close refused to retouch his photographs. His 2009 photo of Brad Pitt for the cover of W Magazine was hailed as the beginning of the end for the Photoshopped model. Today there are brands that declare their stance against alteration as part of their marketing strategies. Do you fear that your aesthetics will be recuperated, as late-stage capitalism is so good at doing?

LB: To an extent, anything that is successful is bound to be redigested. But I remain committed to photography for many of the same reasons I did when I began. As Chris Ware writes of Philip Guston’s late paintings, “they don’t look the way the world looks, but look the way the world feels.” I am interested in this affective possibility of the photograph—specifically the act of photographing, or how taking a photograph places me in the world and in relationship to the object before me. The pictures emerge out of my fascination with that process. If someone is to copy the aesthetic for their own ends, that feels after the fact.

“AS CHRIS WARE WRITES OF PHILIP GUSTON’S LATE PAINTINGS, “THEY DON’T LOOK THE WAY THE WORLD LOOKS, BUT LOOK THE WAY THE WORLD FEELS.” I AM INTERESTED IN THIS AFFECTIVE POSSIBILITY OF THE PHOTOGRAPH—SPECIFICALLY THE ACT OF PHOTOGRAPHING, OR HOW TAKING A PHOTOGRAPH PLACES ME IN THE WORLD AND IN RELATIONSHIP TO THE OBJECT BEFORE ME.”

Z: You have said that you “really like objects that have a pathetic quality.” What draws you to the pathetic? And what makes these objects pathetic, anyway?

LB: It has something to do with potential, something unrealized. I think about Sianne Ngai’s book Ugly Feelings, which explores those unprestigious emotions like envy, anxiety, or paranoia. She unpacks them through literature and it is how I arrived at them as well—or at least how I first started to cleave them away from the personal and get to think about them more formally. For instance, Ngai discusses Herman Melville’s character Bartleby—his refusal to play both a clerk and a protagonist. This kind of character, this kind of difficulty and flat humor, is something I have sought in my pictures. In my studio I am using a conventional scenario, “the photography studio,” to stage a kind of micro-theater. This is a situation that is designed to produce particular object relationships and I am working to undermine these in favor of relationships that feel more urgent, more amplified. When I call them pathetic I mean that they are able to carry all this feeling into a basically transactional space. This is at the center of what I am really up to.

Z: Pathos brings to mind perjury. Photographic evidence is imagined to apprehend life. But you seem to be interested in submitting false evidence. The image as “a bad copy.”

LB: I love that idea—perjury. Back in 2008, when I began making photographs openly using digital tools and the medium’s boundaries were more firm, I felt more capable of pushing up against an established expectation. I had a sparring partner. My perjuries were obvious but there was a sense that they were “bad” information or at least had bad manners. But as indexicality has become more dubious, my work has become about activating something else. In my teaching, I often analogize art photography and poetry; both repurpose an everyday language and do new things with it, stretch it out, give it tension.

Z: Elfriede Jelinek, the Austrian playwright, suggests that “Language must be tortured to tell the truth.” It should be twisted, denaturalized, condensed, cut, made to work against itself.

LB: For me that evokes Werner Herzog. At the turn of the twentieth-century, Herzog outlined his principles of documentary cinema in the “Minnesota Declaration.” Point five: “There are deeper strata of truth in cinema, and there is such a thing as poetic, ecstatic truth. It is mysterious and elusive, and can be reached only through fabrication and imagination and stylization.”

Torturing our tools—be it in the production of words or pictures—has always intrigued me. Everything is inadequate. We have to ask them to do more.

“TORTURING OUR TOOLS—BE IT IN THE PRODUCTION OF WORDS OR PICTURES—HAS ALWAYS INTRIGUED ME. EVERYTHING IS INADEQUATE. WE HAVE TO ASK THEM TO DO MORE.”

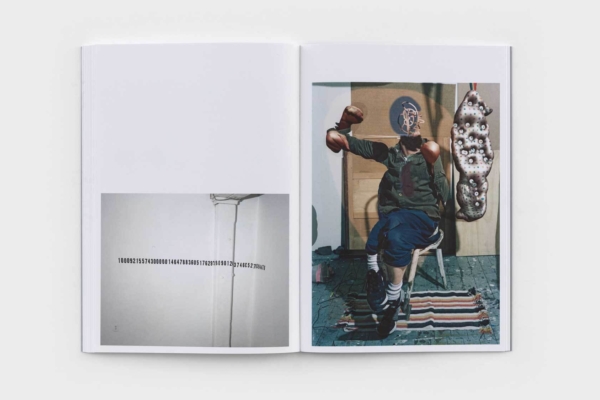

Z: While we are on fibbing, your first book was titled I Believe You, Liar. You have since published several others, including Towards a Warm Math (2011); Mirrors, Windows, Tabletops (2013); and, on occasion of your solo exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art Los Angeles, A Grocer’s Orgy (2019). What calls you back to the book?

LB: The photo is a shitty medium, in many ways. It isn’t the lush object that painting is. It doesn’t have time and sequence the way cinema does. There is a real thinness to it. David Hockney has said, rather snarkily, that we can only pay attention to an image for the amount of time it took to create it; we can thus only look at a photograph for some fraction of a second. I would beg to differ, but there is something there. I have always made books because they allow me to build complex relationships. I think about my work as a web of relations between my intention, my subjects, and my tools; and I think about this as a relational set that evolves over time—and where this evolution is one of the relationships that most characterizes the work. Books have been far and away the best container for laying this out.

If I worked in another medium I don’t know that I would be interested in books but as a photographer they feel like a natural container.

Z: How do you see the relationship between book and exhibition? Is book-making another way of exhibition-making?

LB: They are absolutely different, most so in the way they ask the viewer to use their body. Both are legitimate manifestations of my work, but they are not interchangeable. The scale of a picture on a wall produces a somatic experience unachievable in a book. But books benefit from a scale of their own: A Grocer’s Orgy contained something like a hundred-and-fifty images. I could never achieve that density in an exhibition.

Also, whereas exhibitions are rotated every few weeks or months, books stay around. You can get to know them. I fell in love with so many artworks that I love through books. I have been fortunate to see many of these in person since, but it often starts on a page.

Z: How does it feel to experience a work in the flesh that you have only known in a book?

LB: My god. It can go so many ways. Sometimes it is terribly disappointing. Other times you have the scale all wrong. And yet others it can be astounding. The potential for an emotional experience is so much greater in front of the object. Museums are cool; I miss them right now [in quarantine].

Z: As museums and galleries have shuttered their doors in response to the coronavirus, many staged virtual exhibitions. Are you interested in showing your work virtually?

LB: I am in a virtual exhibition currently, and will participate in another next month. I have long been interested in the properties of translation as you pull something out of an immaterial space into a material one, and vice versa. But working in a medium that is, at this point, native to the virtual, exhibiting my images online doesn’t have much of a charge.

I have never seen a virtual exhibition that I loved. So much of what pictures do in person is absent.

Z: If you weren’t an artist, you would “be a writer. Or just something exhausting, like a boatsman.” Do you think of photography and writing as distinct activities? Or do they somehow exist together?

LB: They are separate activities, though I like them for a lot of the same reasons: photography and writing are both everyday; they are both inadequate; they have all sorts of limits and walls; they can be beautiful but you can feel their edges easily. I have learned a lot about photography through writing and certainly from reading, and I have learned about writing through photography. But doing them is different; they turn on distinct parts of my brain.

“PHOTOGRAPHY AND WRITING ARE BOTH EVERYDAY; THEY ARE BOTH INADEQUATE; THEY HAVE ALL SORTS OF LIMITS AND WALLS; THEY CAN BE BEAUTIFUL BUT YOU CAN FEEL THEIR EDGES EASILY. I HAVE LEARNED A LOT ABOUT PHOTOGRAPHY THROUGH WRITING AND CERTAINLY FROM READING, AND I HAVE LEARNED ABOUT WRITING THROUGH PHOTOGRAPHY.”

Z: Alexandre Astruc suggested the “camera-stylo”: that directors should wield their cameras like writers use their pens. And Jean Luc-Godard declared that “La Camera, C’est L’ecran.” “I think of myself as an essayist,” he said in 1962, “I write essays in the form of novels or novels in the form of essays: but I merely film them instead of writing them. Were cinema to disappear I’d accept the fact: I’d shift over to television, and were television to disappear, I’d go back to paper and pencil.”

LB: I admire Astruc and Godard, and I recognize the connections between film and writing. For me, photography’s lack of temporality makes it different. A single photograph is monosyllabic. It can make a sound or, at best, it can make a sentence. That is all it can do. Language unfolds over time; it has no other choice.

LUCAS INVITES YOU TO READ:

- Towards a Philosophy of Photography, Vilem Flusser

- Our Aesthetic Categories, Sianne Ngai

- A Series of Utterly Improbable Yet Extraordinary Renditions, Arthur Jafa

- Mimesis and Alterity, Michael Taussig

- The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study, Fred Moten and Stefano Harney

- Ubik, Philip K Dick

- The Babysitter at Rest, Jen George

- Manifestly Haraway, Donna Haraway

- Frankenstein, Mary Shelly

- Virtual Memory: Time Based Art and the Dream of Digitality, Homay King

- The Emergence of Social Space, Kristen Ross

- Humiliation, Wayne Koestenbaum

- As Painting: Division and Displacement, eds. Philip Armstrong, Laura Lisbon, Stephen Melville