MAY CASTLEBERRY

ON PUBLISHING ARTISTS’ BOOKS, THE STRANGE JOY OF CATALOGING, AND THE FUTURE OF THE LIBRARY. —08.01.2019

May Castleberry is editor of a series of artists’ books published by the Library Council of The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): What do you read when you are not publishing the likes of Olafur Eliasson, R.H. Quaytman, and Beatriz Milhazes?

May Castleberry: I read whatever I’m handed, really, which is mostly non-fiction. My husband is an art historian—a Picasso scholar. He’ll be teaching in Barcelona this year; all the books to be found in our living room seem to concern the Spanish Civil War right now. My son is a budding ecologist, and books on natural history are everywhere.

Also, so much passes through your hands when you work in an art library—as I have since prehistory. In a library, there’s a great deal of learning by...

Z: By osmosis?

MC: Yes, that’s it. When I started as a librarian at the Whitney in 1979, I was the only staff member for a library of 10,000 volumes. I was 23. It was not a great job—and very poorly paid. I was in charge of all things, including our annual inventory. So I would pull each and every book off the shelf, every year to make sure it had not been lost. Drudgery, yes, but I’ve come to realize that just putting book after book in my hands introduced me to the vast possibilities of the medium.

“WHEN I STARTED AS A LIBRARIAN AT THE WHITNEY IN 1979, I WAS THE ONLY STAFF MEMBER FOR A LIBRARY OF 10,000 VOLUMES. I WAS 23. IT WAS NOT A GREAT JOB—AND VERY POORLY PAID.”

Z: Was the Whitney collecting artists’ books when you arrived?

MC: At that time it was predominantly exhibition catalogs and art historical books. In the early ‘80s the museum was starting to make money and our Library budget grew, at least enough for us to embrace the acquisition of books by artists. Artists’ books of the ‘60s and ‘70s were so cheap—at that time they were increasingly appreciated, but still affordable. Up until about 1985, signed copies of Ed Ruscha’s and Bruce Naumann’s artists’ books were still around and could even have been mistaken for a drug on the market. Earlier artists’ publications were appreciated by an even smaller niche of dealers and collectors at the time. I was able to acquire for the Whitney Museum a full-set of VVV, the official organ of the Surrealists in Exile, in beautiful condition—I think it was $250?

Eventually, as more money came into the Library budget (thanks to donations), I was able to devote more of my time to exploring bookstores and other libraries in New York and elsewhere in the Northeast. It was a privilege to see so many books; this experience helped me understand the book form’s never ending possibilities for artistic experiment.

Z: The Whitney and MoMA (where you now work) are gatekeepers to the Modern art canon. Their libraries are, by extension, something of the same for artists’ books. How do you decide what to include—and not include?

MC: One constant at museums like MoMA and the Whitney: they are lucky enough to be presented with an enormous number of gifts and offers, and yet, at the same time have limited budgets with which to buy, catalog, and house books. At MoMA, two departments acquire artists’ books. One, the Department of Drawings and Prints, which has a long history of acquiring livres d’artistes, brings in select artists’ books. An acquisition for the Museum’s collection requires the advocacy of curators and the agreement of a committee. The MoMA Library collection (not considered as part of the Museum collection) is more open, and in some good ways, complementary to Drawings and Prints. The Library accepts most gifts of artists’ books. Working with a limited budget, it tries to buy books that seem to be relevant to the curatorial program—or that are highly innovative in the field of artists’ books. But some wonderful books always fall between the cracks, or do not get cataloged for a long while.

Long ago, at the Whitney Museum between 1980–2000, I acquired artists’ books and all other books for the Whitney Library. Many purchases reflected the curatorial program but there was usually an opportunity to buy some artists’ books that stood out as historically important or particularly innovative, to my mind. Sometimes the staff hid behind arbitrary criteria (for example, we admitted to only buying books by artists who have already been shown in the Whitney galleries) in order to keep our heads above water. I’m not sure what the Whitney does now—the library space is smaller than it was when I was there. It can’t be easy.

When I went to MoMA in 2000, I left bibliography behind to focus on editing and publishing. As much as I love collecting books, I was relieved to no longer be worrying about what we could afford to buy, catalogue, and protect, or not. There are wonderful people doing that in MoMA’s Archives and Library. The Library Council is there to support their efforts.

Z: You’ve said that you have the “privilege and challenge of working with artists and other collaborators to produce artists’ books?” What are the particular challenges of editing and publishing artists’ books?

MC: Even as a grizzled veteran, I know that every artist presents a challenge that I haven’t encountered before. The artist’s book is at its best when it rethinks the very form it takes. And that’s the ultimate challenge. You have to let the artist go out on a limb, explore it, and, as the editor, you have to follow them out on it to try to determine whether the limb will break or not. It’s always surprising.

“THE ARTIST’S BOOK IS AT ITS BEST WHEN IT RETHINKS THE VERY FORM IT TAKES. AND THAT’S THE ULTIMATE CHALLENGE.”

You can’t predict anything. You just have to hope you can support an unexpected turn in a project, and attempt to stay sane.

Z: In book publishing there is an editorial contract between the writer and publisher—that the writer will pen their text and the publisher will then offer suggestions, shuffle the structure, add oxford commas, and the like. That same contact is not built into visual art. The tradition of old masters correcting their students’ paintings is long gone.

MC: Wouldn’t you love it if an old master would come in and do that! But to your point: yes, writers are used to spending a great deal of their careers in conversation with editors, and in conversation with the world. They usually think a discussion, at least, with an editor might make their material better. As for visual artists, the spectrum is broad indeed.

On one end, there are painters and sculptors who are relatively new to the book form and rarely collaborate. Their galleries may have even built a shrine to their solitary ego (and why not). I have to tell the truth: it can sometimes be difficult. Peter Schjeldahl once said, “artists: licensed psychopaths.” I think I know what he meant!

On the other end of the collaborative spectrum, there are artists (like Andy Warhol, Ed Ruscha, Tauba Auerbach, Olafur Eliasson) who were originally trained or excel as designers. Early on, they began listening to and collaborating with artisans, printers, manufacturers, and other designers. If and when they need to talk to a publisher or editor, they understand how this might benefit a project.

Z: Did raising a kid teach you how to edit an artist’s book?

MC: Oh, yes. And editing has taught me about parenting. Or not!? This reminds me of a quote from a colleague about the New Yorker Editor Katherine White: “As an editor, she was maternal, and as a mother she was editorial.” Her son, the writer Roger Angell, said that if only he’d heard this comment earlier in his life, he would have saved himself a fortune in psychiatriatric bills.

“‘AS AN EDITOR, SHE WAS MATERNAL, AND AS A MOTHER SHE WAS EDITORIAL.’”

Z: When does a book become an artist’s book?

MC: Who knows who can draw that line. Perhaps it has something to do with play. Conscious play. Testing the limits of the form. Teasing the rules. Cutting into image and text. Eschewing the conventions of reproduction. The art book presents a work as document. The artist book is something else entirely.

Z: With the artist’s book, the project is the page.

MC: Exactly.

Z: The Valise, your 2017 project with seven South American artists and Argentine writer César Aira, abandons the cover to cover format of the book altogether. Is it still a book? Why did it demand that form?

MC: I’d say it is a book-like thing. It had always seemed to me that books are the perfect medium for recording travel. Indeed, there is a rich history of eighteenth-century exploration ledgers and nineteenth-century travel logs. I was looking for a way to bring a group of artists together, especially younger artists, around this age-old form. At first I thought it could be from various continents, but then got some excellent ideas from MoMA’s then-curator of drawings, Luis Pérez-Oramas. I had already noted that many emergent South American artists were especially concerned with geographic and physical exploration; he enthusiastically agreed and helped me define and expand this collective project.

Z: You published your first book, Fables, Fantasies, and Everyday Things: Children’s Books by Artists, with the Whitney in 1992. Before the e-book, the PDF, and the editorial migration to the screen. What is the role of the printed book today? Why do you remain committed to the form?

MC: It is amazing you found that. Fables, Fantasies, and Everyday Things was such a fun project. Well, speaking of children’s books, we’ve all had a pre-literate experience with the page. Before we know how to read the characters on it, we touch it, we turn it over, we get to know it sensorially. That is a type of reading, too. Whether we remember it or not, I believe that tactility resonates for the rest of our lives.

What will happen, I wonder, when children no longer have that experience with a physical text?

Z: The infant who reads Goodnight Moon on the iPad.

MC: Yes, that’s a scary thought. Though the way that we read on the iPad was sort of shaped by the book, you could say.

Z: Well, it is a facsimile of the print experience. We haven’t liberated the digital text from its prior materiality. The book is stubborn; it has not fundamentally changed since Gutenberg’s incunabula.

MC: It is just the best medium. So rich. When I start a new project with an artist I’ll take them to see rare books—seventeenth-century alchemical texts, scrolls, all of it. There are more ideas in the history of the printed page than most people could possibly imagine. Boundless room to invent.

Z: In postwar Europe, the artist’s book was hailed as a “democratic” form—made possible by the advance of printing techniques and, by mid-century, the advent of photocopy and offset production. Pamphlets, zines, and codexes circumnavigated the gallery and museum infrastructure. Today, many artists’ books are published by those institutions, and decorate the tables of those who can access the works they involve. Has the artist’s book been swallowed by the system it was created to escape?

MC: Artists will always think of a new, subversive form of book. But yes, in answer to your question, it’s all too easy to forget when something has been swallowed by the system. When I hear a MoMA curator talking about the transgressive nature of an object in our collection as a contemporary fact, I am reminded that by endorsing an artifact, we have in some sense altered it. I hope and expect there are many things happening outside the Museum that the Museum doesn’t know about and wouldn’t accept.

Z: The MoMA, in fact, held an exhibition of artists’ books—The Century of Artists Books—in 1994.

MC: Yes, Riva Castleman curated that show. The catalogue is a great document for the history of the livre d’artiste. Deborah Wye (then a MoMA curator who later succeeded Riva Castleman as Chief Curator in the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books) contributed to the exhibition and catalogue, as did Clive Phillpot, the then-Chief of the MoMA Library and artist’s book thinker extraordinaire. Debbie and Clive built the case for the artist’s book as a distributable, activist medium—one that could be argued was not part of the market.

Almost all things loved by the art world have a way of becoming monetized collectibles. As accustomed as I am to market phenomena, I am still surprised when I see major galleries publishing artists’ books. I have mixed feelings, as there is every reason for artists to make a great book as a work of art, published by their gallery. Yet, on another level, their purpose could not be more conflated with the sale of big-ticket paintings and sculptures. (I’m dating myself—as if I haven’t already!)

What most protects the artist book is its relative humility. Whereas collectors of painting and sculpture may proudly present themselves on Instagram, standing in front of a trophy acquisition, book collectors circulate images of artist’s books as a kind of secret invitation to learn more. Book collectors tend to be introverted.

“WHEREAS COLLECTORS OF PAINTING AND SCULPTURE MAY PROUDLY PRESENT THEMSELVES ON INSTAGRAM, STANDING IN FRONT OF A TROPHY ACQUISITION, BOOK COLLECTORS CIRCULATE IMAGES OF ARTIST’S BOOKS AS A KIND OF SECRET INVITATION TO LEARN MORE.”

Z: The artist’s book denies the possibility of spectacle. It offers, instead, more intimacy, more contemplation.

MC: The best artists’ books are irreducible. They unfold with you. They tell complex stories, using the element of time and space like no other medium.

Z: The artist’s book seems to approach the American artist Donald Judd’s idea of the “permanent installation.” Of Chinati, his site in Marfa, Texas, he wrote that “It takes a great deal of time and thought to install work carefully. This should not always be thrown away. Most art is fragile and some should be placed and never moved again.” Art demands that we come back to it, spend time with it. The book allows that.

MC: I agree. My bias is for the book.

Z: Producing and distributing books—particularly the glossy, inky, heavy-stock artist variety—is not without its costs, though. The publishing industry consumes about 11% of freshwater reserves in industrial nations. Why do we—why should we—continue to run the presses in the face of ecological collapse?

MC: It is such a tough question—a good and important question. I can’t answer that. I think it is a great deal of it is ignorance. We’ve been far too ignorant, for far too long. I just read Alan Weissman’s review of David Wallace-Wells’ The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming. I must go out and buy it. You want to say, Let us stop and consider every single thing we’re doing.

I would love to make an artist book with a great natural historian. Someone like Tim Flannery, the Australian paleontologist. A book that would be at once artistic and environmentally edifying. It’s a tall order.

Z: I’ll hold you to it. Do you have a favorite place to read?

MC: I’ve spent a lot of time in just a few libraries. I wish I’d been to more. The Pompidou’s library was great. The New York Public Library was fantastic—still is. And then I might say our library at the MoMA. The structure itself is fine, if not a little austere. But the Library reading room looks out onto 54th Street and the sculpture garden, and in that way is really serene. The Archives reading room peers out at the stained glass of the nearby church. It’s an ecclesiastical view.

Z: So deserved for the holy work of archiving. What do you hope the library of the future will look like? More stained glass?

MC: The library should always evolve. I do hope that, whatever happens, it will still have tons of books. And that it will keep out the noise. That’s the one thing. I just need some quiet—but I guess that is a cranky old-person’s thing to say. We just need a place to think.

“THE LIBRARY SHOULD ALWAYS EVOLVE. I DO HOPE THAT, WHATEVER HAPPENS, IT WILL STILL HAVE TONS OF BOOKS. AND THAT IT WILL KEEP OUT THE NOISE.”

Silence grows more and more precious. Jennifer Tobias, our research librarian at MoMA, scolds me whenever my phone goes off. I just have to thank her for that. Thank you for taking care of this space.

I recently visited the wonderful exhibition on the Moon, Apollo’s Muse, at the Met. There’s a room dedicated to Neal Armstrong’s moon landing, with NASA photographs, accompanied by the crackling sounds of the NASA to Apollo radio transmissions of the landing. The problem was, you could still hear the moon landing sounds in an adjacent room, filled with visionary nineteenth-century paintings and drawings of the moon. A classic exhibition design problem, not yet solved.

I think sensory perception is our next frontier. Soon they say that planes will, instead of just waking you up on a trans-Atlantic flight, slowly increase the intensity and change the hue of the light the way your brain would prefer.

Z: When the cabin lights come on, it’s like you have woken up in a hospital.

MC: Oh, and hospitals. People do not get rest in hospitals. But, leaving aside hospitals, we need more people to think through the neuroscience of the library experience.

Z: The library becomes the laboratory. The place where we are prototyping solitude.

MC: Yes, good idea. We’ll start that.

Z: In Norway, the Svalbard Global Seed Vault “ensures against the loss of seeds during large-scale regional or global crises.” If we were to start an Arctic book vault to preserve our most important ideas and language, what would you put on the shelf?

MC: I would recommend some tactile things. Our alien visitors ought to know that reading a book is about more than the text. It’s a joy of so many sensations.

“OUR ALIEN VISITORS OUGHT TO KNOW THAT READING A BOOK IS ABOUT MORE THAN THE TEXT. IT’S A JOY OF SO MANY SENSATIONS.”

MAY INVITES YOU TO READ (AND SEE, AND TOUCH, AND FEEL):

- Japan: A Photo Theatre, Daido Moriyama

- Nella Notte Buia / In the Darkness of the Night, Bruno Munari

- Métal, Germaine Krull

- Eis, Gerhard Richter

A few of the tactile books published by MoMA’s Library Council, such as:

- The Island of Rota, Ted Muehling, Abe Morell, and Oliver Sacks

- Tom Tit Tot, R.H. Quaytman and Susan Howe’s

- Time Bomb, Charles LeDray’s miniature book collection.

Note: these books, and many others, are available on request in the MoMA Library.

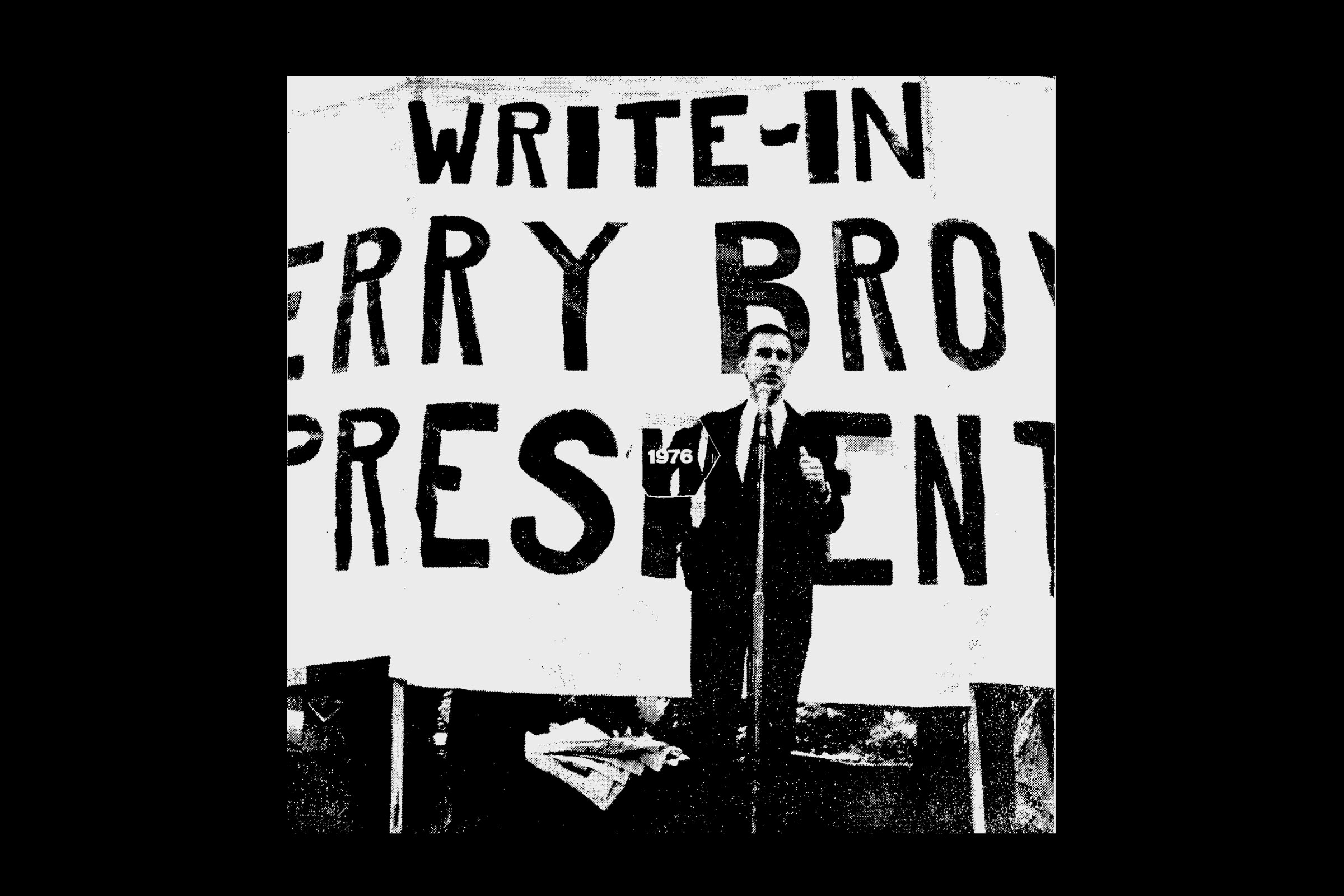

Illustration: Write-In Jerry Brown President, Doug Aitken. Published by Library Council of The Museum of Modern Art.