ANN BOBCO & B. WURTZ

ON CHILDREN’S BOOKS, ARTISTS’S BOOKS, AND A YOGURT CONTAINER. September 20, 2019

Ann Bobco (b. 1954, Denver, Colorado) is a reader, bookmaker, and a former Executive Art Director at Simon & Schuster Children’s Books.

B. Wurtz (b. 1948, Pasadena, California) is a sculptor of everyday things.

Robert Morris Levine (for Zolo Press): B., who is Ann Bobco?

B. Wurtz: That’s something I’m still figuring out. In many ways I do know but there are things I’m learning. Well, for one thing, she’s an image-and-word person.

Ann Bobco: Okay, but I prefer something a bit less restrictive, maybe something like: Ann Bobco is “a person working on becoming more human.”

BW: We met in graduate school at CalArts in 1979. We both have MFAs in what John Baldessari had coined as “Post-Studio” degrees. When Ann was there she was making conceptual work; some of it took the form of books. She had many interests and after graduating decided she didn’t want to go into visual arts. Instead she transitioned to graphic design, which brought her to magazines and, eventually, back to books—children’s picture books. That totally made sense to me. For over twenty-five years she art directed and designed picture books for young readers within several imprints at Simon & Schuster. She made me see how a picture book story is best conveyed “synergistically,” where the text and the art act in an interdependent manner to offer a fuller experience than either could offer on their own.

Z: And Ann, who is B. Wurtz?

AB: B. Wurtz is someone who has a strong interest in the world as it exists visually. When we are out and about he is always pointing to something in view that draws his attention. And then there’s music, both listening to it and the making of it. That is part of his make-up as well. There are many other aspects I could mention but that might turn into a biography. And that’s not for today. (Ha!)

Z: What was the first book you read together?

AB: You know [gesturing to B.].

BW: What?

AB: Well, we didn’t read it together, but… it was The First and Last Freedom.

BW: Oh! Yeah. I thought I didn’t know the answer. When I first met Ann she loaned me that book by J. Krishnamurti. His books are typically shelved under Eastern Religion, because bookstores don’t know where else to put him. I would place him under Philosophy. Anyway, Ann loaned it to me. I thought, Oh, I’m not going to be into this; this is another one of those sixties guru-types. I read the first page and he said something like, Let’s just talk about some stuff together. It was so different from what I’d expected. I finished it and it had a huge impact on me. I really think Krishnamurti was enlightened—he got it.

“ANN LOANED IT TO ME. I THOUGHT, OH I'M NOT GOING TO BE INTO THIS; THIS IS ANOTHER ONE OF THOSE SIXTIES GURU-TYPES.”

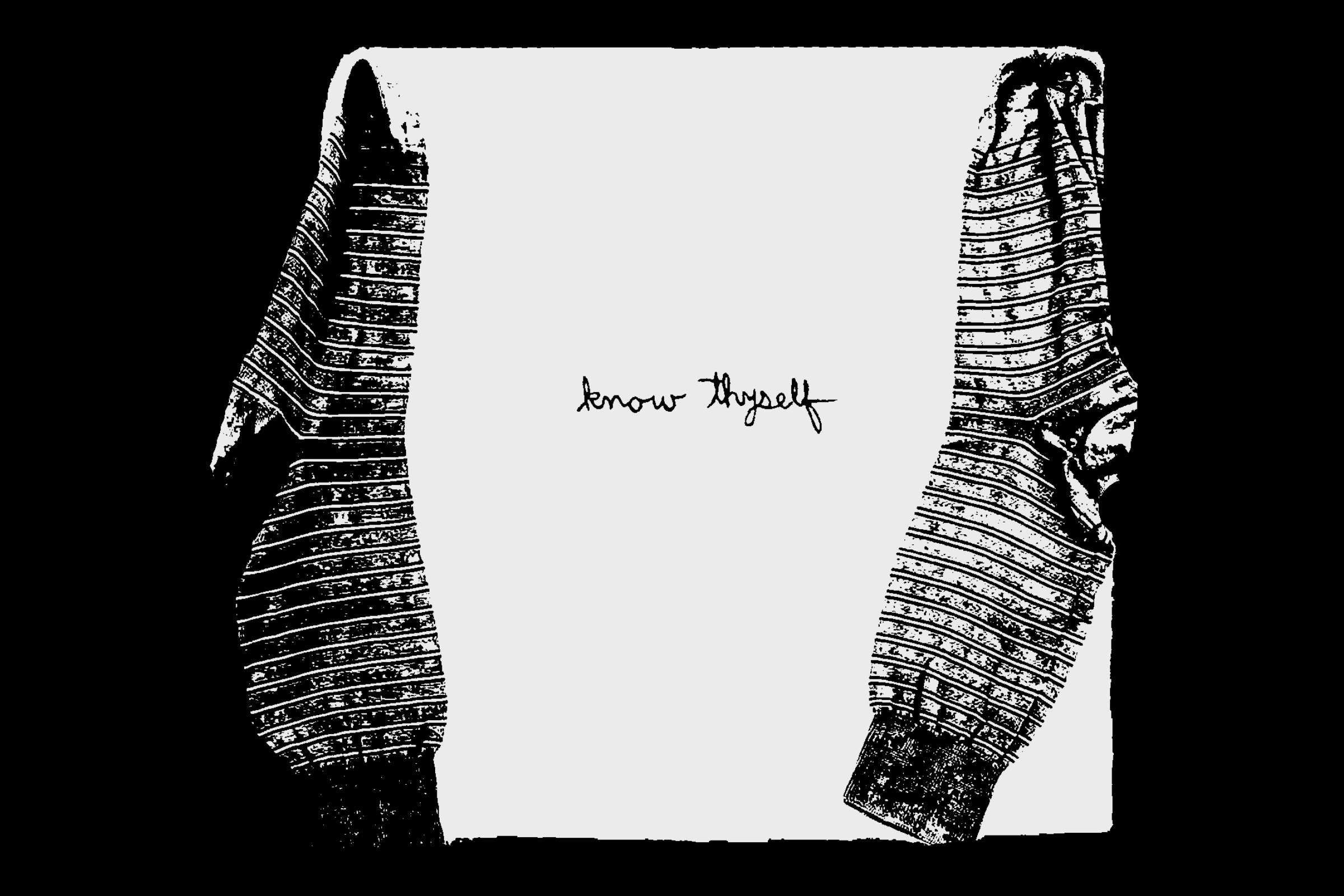

A lot of the text I use in my work comes from his writings. This Has No Name was the title of my show at the ICALA in 2018. “Know thyself ” is a phrase I relate with Krishnamurti, too. What’s so strange is that I recently reread that book and got even more out of it than the first time.

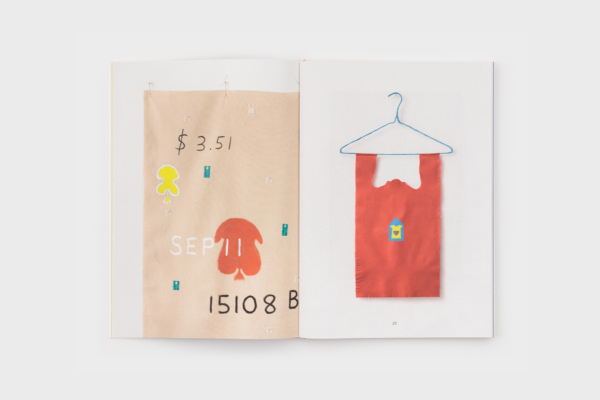

Z: You use text throughout your work, B., much of it from packaging and plastic bags, not philosophy. For instance, you’ve incorporated that Stonyfield yogurt container on the dishrack [pointing across the studio] into many of your pieces, rescuing it from mundanity (or at the very least the trash). When you bring that operational text into your sculptures it becomes something else.

BW: Yes! Maybe something like poetry. I’ve always been interested in language. I’m now writing songs with lyrics, which I’ve never done before.

Z: Years ago, when you were working freelance jobs, you would be in charge of composing slides for business presentations. Did your exposure to corporate-speak inform how you think about language?

BW: Mmmm… maybe. I use words and language in two ways. One: I write things myself. Like “Sleeping, eating, keeping warm.” Or: “know myself”— well, I mean, I didn’t write that! But then I often do engage in a Duchampian readymade use of language. For example, you can see it in my use of the text on containers and boxes and bags, which I just present as is. I don’t change the language because it is a part of the (found) object. By bringing it into an artwork, those texts are transformed like “assisted readymades.” Hm! I’ve never quite thought of it that way.

AB: That reminds me of something: when I first met Bill in 1979 he was installing work in the main gallery at CalArts. B., you had images from Peter Brown, right—

BW: Yes. My friend Peter Brown worked in advertising and every once in a while he’d give me outtakes of product shoots. Transparencies.

AB: They were large transparencies, maybe 8 x 10? And they had stuff written all over them.

BW: Right! Words like “re-shoot.” I kept the hand-drawn language scribbled in grease pencil as part of those artworks.

AB: One of the things that fascinated me about Bill early on was hearing different takes by other artists on his work, including those pieces. I remember John Mandel saying, “Oh, I get it. I see. His work is all about presentation.” Bill had taken those large transparencies and constructed beautiful wire suspensions for them. I loved that. Now, forty years later, I see more clearly how John didn’t find the work compelling at all (as was his right, of course)!

BW: I use my own name as text too. I often sign my name on the front of artworks. I got shit for that at CalArts.

Z: Why?

BW: It was considered unseriously anti-conceptual or something. Like the most crass thing I could do. Of course that made me want to do it all the more. But I did it for a reason. Years before I had shortened my first name (my art name, not my legal name) to the initial B. and it became a persona. A rather anonymous, androgynous persona. As a kid I saw that Picasso signed his name on the front of all his paintings and I just started doing that from the time I was young. But I wasn’t oblivious to rethinking it. I don’t always put my name on the front of an artwork. It depends what I want it to do for the piece.

“IT WAS CONSIDERED UNSERIOUSLY ANTI-CONCEPTUAL OR SOMETHING. LIKE THE MOST CRASS THING I COULD DO. OF COURSE THAT MADE ME WANT TO DO IT ALL THE MORE.”

As a side-note: I was fascinated by examining myself. What made me become an artist? What was it in my brain that made me do this, instead of that? At the end of the ’70s at CalArts there was an ongoing discussion of Critical Theory and the Frankfurt School and such. I was interested to hear about art’s social and political influence as described by various philosophers but ultimately decided that political ideology didn’t belong in my art making. My work has always come from a personal place and if it has a “meaning” it’s in how the viewer receives it.

Z: You authored your first book, Blocks, in 2006. “Like Japanese bonsai and actual trees,” you say, “blocks, the children’s toy, relate conceptually to full-sized buildings. Scale and stories become otters of imagination. A little block can be a mirror to the whole world.” I can’t help but sense Ann’s shadow here, with her devotion to children’s books.

BW: I’ve always played with the childlike. What Ann did was teach me about graphic design. When I did Blocks I used some of the skills I’d learned from her—text on a page, and stuff like that.

AB: Hm, I don’t have anything to offer in terms of Blocks’s relationship to children’s books. But I will say that one of the things I like about the book is how when B. was working on it, it made me think of other of his appropriations of some of Baldessari’s pieces.

Z: Who you both studied under at CalArts.

AB: Yes. I think Baldessari only blocked out human faces, though. With Bill and his Blocks book there are windows and other inanimate elements obscured. That formal device is delightful to me; it’s a way of hiding something while pointing to it at the same time.

BW: I remember how I wrote Blocks. I made up sentences about ordinary acts. “Somebody mops the floor.” “Someone is angry at his boss.” “Somebody reads her book.” Then I plugged in the names of various people I knew. I enjoyed introducing that very personal element which no one else would recognize. It was fun tying these real people’s names to a range of daily, sometimes humdrum activities or states. Like a Dada, John Cage text: “Carl makes a salad.” “Jean has the flu.” “Daniel is eating.”

Z: You published Blocks in 2006 with Onestar Press, then Food and Watercolors in 2012 with Publication Studio. And, of course, there was Philosophy from B to Z with Zolo Press in 2018. You’re on a six-year rhythm. What calls you back to the artist’s book now and then?

BW: I never decide that I want to do an artist’s book. It’s basically that invitations come to me. I’m lucky. They come to me. Yay!… Onestar invited me. I must have been invited by Publication Studio. That might have had to do with my going to Portland, Oregon, where a friend of mine—Arnold Kemp—was teaching at the time. He connected me with them. And then I met Arno [from Zolo] in Mexico City when I was doing the show at Lulu. Each book developed in its own particular way.

Here’s a roundabout bit of backstory related to Philosophy from B to Z, which was a wonderful collaboration. I often prefer not to install my own work. The curators / gallerists know what they’re doing in terms of installing art, so I enjoy—perhaps again inspired by Cage—letting them at it. If I had to, of course I could take my work, set it up in a space, and make a show. But often, other people are better at that than I am. It ends up being a surprise for me. Many artists don’t think that way. The installation of their work is actually part of their work. That’s not my interest, though. Ohhhh, sorry — that was a long backstory! Let me just say that Arno took my work and ran with it in terms of his design. He was able to capture the spirit of my art in a book and prove how the best example of collaboration results in an experience beyond just the sum of its parts.

Z: Cage might applaud you; Judd might scold you.

BW: Ha! Okay, but Judd was really, really good at installing his work. In fact, that was a large part of his production and it made sense for him to install it. I would never criticize him for that. But, as I’ve said I relate to what I’ll paraphrase as the John Cage approach: be open and you are enriched by what you wouldn’t expect.

Z: Your I Ching is inviting people in.

BW: I guess, but I’m not an idiot! If I don’t trust the person, I’m not going to do it, but if someone knows what they’re doing, I’ll gladly let them. And it’s really fun for me.

As I mentioned to you earlier today, I’m writing songs now, working with a wonderful producer in Los Angeles. I send him my tracks and he adds other instrumentation, then we go back and forth. It’s a true collaboration. And it’s thrilling. They are still my songs, but I really don’t need to do everything.

Z: Is that how your relationship works?

AB: When it works, sure!

BW: Haha. Yes!

AB: We’re both very controlling individuals—unlike 99% of the rest of the world!

BW: I want Ann’s opinion about my work. I don’t always agree but I know she’s going to be direct with me and that it’s going to be useful. Even if I disagree it’s still useful.

AB: I’m used to that. A number of people disagreed with me when I’d make suggestions for children’s books [at Simon & Schuster]. I blame that in part on my inability to persuade, of course. But for instance, I contacted the artist Kay Rosen to see if she’d be interested in developing a children’s book of her own making—and she was interested—but when I showed her work to the publisher it became clear that it would never happen. She was perceived as being “too sophisticated” but I think working with a good editor could have landed a strong, imaginative book for young readers. The publisher wasn’t convinced. At another point I suggested one of our author-illustrators consider developing a picture book biography of Sister Corita. I’ve always thought Sister Corita / Corita Kent was amazing. When Corita was teaching at Immaculate Heart College in Los Angeles during the 1960s she brought so much to those students! She knew Charles and Ray Eames and brought them, as well as artists such as John Cage, to visit her classes. I thought, and still think, her openness in how she looked at the world could be accessed by young middle-school kids. I love one of the assignments she gave her students where she took them outside for a day and gave each one a big white piece of paper with a large window cut into it. She had them walk around the city, “framing” different parts of what they saw. I thought it would be such a nice element in the book to include a detachable white frame like that. Initially the author-illustrator I’d approached was interested in the prospect of the book but then expressed resistance because of the religious content of some of Corita’s work. At this point in time I’ve left that publisher and hope the book materializes in the future.

“SHE TOOK THEM OUTSIDE FOR A DAY AND GAVE EACH ONE A BIG WHITE PIECE OF PAPER WITH A LARGE WINDOW CUT INTO IT. SHE HAD THEM WALK AROUND THE CITY, ‘FRAMING’ DIFFERENT PARTS OF WHAT THEY SAW.”

Z: Many artists have made children’s books. Kusama with The Little Mermaid in 2016. Chagall illustrated Yiddish children’s tales. Hockney. Bearden. Dali. Faith Ringgold. It seems to me that the children’s book is the cousin of the artist’s book. It discards prescribed dimensions, luxuriates in tactility, considers all the senses.

BW: Lawrence Weiner did some children’s books, too.

Z: Why are artists interested in books for kids?

AB: Who really knows? Creativity is a state of being that hovers between unselfconsciousness and self- consciousness. The best artists negotiate those two planes. The best picture books for children do as well. Since one’s imaginative capacity needs feeding, the draw to “books for kids” (as you call them) might be the strong images, or the sense of story, or the actual story. There may be concepts that feel unencumbered by social restrictions or worlds that seem simultaneously familiar and unfamiliar. It seems to me that the idealization of childhood can’t help but hold sway in this seduction.

Z: The children’s book invites you to play around.

AB: Yes/But. “Yes,” because the invitation to play is always present. “But,” because having genuine freedom to produce a strong children’s book within conventional publishing is really difficult. There is a conservative component to commercial publishing for kids that has existed for many decades, maybe always, in this country. The market for children’s books is held at bay by gatekeepers such as librarians, school teachers and more obviously in these times, by the politically correct police that can be found nearly everywhere. However there have always been wondrous exceptions.

Z: Like children’s books, artists’s books invite us to make them our own. We can bring them home, cozy up with them.

AB: I think artists’s books have so much potential. (Yikes, what an obvious thing to say: “potential.”) They allow for a relaxed amount of rambling alternating with sustained attention. That can help to foster an intimacy required to know an artwork for one’s very own self. People often cast art aside as something just for fancy-pants people. I love to think that anyone who can physically handle and look through an artist’s book can do so without prejudice. It requires confident curiosity. There’s no right way to receive art because we as the viewer are the third part of the triad for reception. The first of the triad being the maker, the second being the object itself, and the third (completing the circle) is the viewer.

“I THINK ARTISTS’S BOOKS HAVE SO MUCH POTENTIAL. […] THEY CAN HELP TO FOSTER AN INTIMACY REQUIRED TO KNOW AN ARTWORK FOR ONE’S VERY OWN SELF.”

Many of us acknowledge that art is a distant cousin of craft and as such is something most people, but definitely all cultures have a history of making—in spades. Making marks and objects, making meaning and such—despite the rarified world of modern cultural production—is something that will remain with us until there is no “us” left on this planet.

BW: I agree. A book is a thing. Something people can pick up. No guard will yell at you for touching it!

ANN AND B. INVITE YOU TO READ:

- The Baudelaire Fractal, Lisa Robertson

- Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead, Olga Tokarczuk

- In the Distance, Hernan Diaz

- The Miracle of Analogy: or The History of Photography Part 1, Kaja Silverman

- War and Peace, Leo Tolstoy

- Warhol, Blake Gopnik